| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

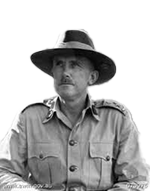

Frank Horton Berryman was born in Geelong on 11 April 1894, the fourth of six children and the eldest of three sons of William Lee Berryman, a Victorian Railways engine driver, and his wife Annie Jane née Horton. Frank was educated at Melbourne High School where he served in the school Cadet Unit and won the Rix Prize for academic excellence. On graduation he took a job with the Victorian railways as a junior draughtsman.

In 1913, Berryman entered the Royal Military College (RMC) Duntroon having ranked first amongst the 154 candidates on the entrance examination. Of the 33 members in his class, nine died in the First World War, and six later became generals. Berryman rose to fifth in order of merit before his class graduated early in June 1915, because of the outbreak of the First World War.

Berryman was commissioned as a Lieutenant in the Permanent Military Forces (PMF) on 29th June 1915 and again in the First AIF on 1st July 1915. He was posted to the 4th Field Artillery Brigade of the 2nd Division Artillery and embarked for Egypt with the 4th on the transport Wiltshire on 17th November 1915. In Egypt, Berryman briefly commanded the 4th Brigade Ammunition Column before it was absorbed into the 2nd Division Ammunition Column.

The 2nd Division moved to France in March 1916. Berryman became a temporary Captain on 1st April 1916, and was made substantive Captain on 10th June 1916. In January 1917, he was posted to the 7th Infantry Brigade as a trainee staff |

Captain. During the Second Battle of Bullecourt he served with 2nd Division Headquarters. He was appointed to command the 18th Field Artillery Battery and became a temporary Major on 1st September 1917, which became substantive on 10th September 1917. This was as far as he could go, for Duntroon graduates could not be promoted above Major in the AIF. This policy was aimed at giving them a broad range of experience, which would benefit the Army, while not allowing them to outnumber the available post-war positions. While commanding the 18th Field Battery, he saw action at the Battle of Passchendaele. For his service as Battery Commandeer in this battle he received a Mention in Despatches. In September 1918 he was awarded the Distinguished Service Order for his service as Battery Commander of 14th Battery from 8th May until September 1918.

Berryman was later nominated for a bar to his Distinguished Service Order for the September 1918 fighting, but this was subsequently downgraded to a second Mention in Despatches. He was wounded in the right eye in September 1918 while he was commanding the 14th Field Artillery Battery. Although his wound was serious enough to warrant hospitalisation, there was not permanent damage to his vision. He was subsequently posted to a staff position and from 28th October 1918 to 1 July 1919 he was Brigade Major of the 7th Infantry Brigade. Berryman returned to Australia in October 1919. In his eulogy at Berryman’s funeral, Lieutenant General Sir Donald Dunstan remarked that it was said of Berryman’s Second World War service that “his victories were built on solid foundations of farsighted training; smooth organization, careful planning and (he) had a genius for such things”.

Berryman was appointed to the Staff Corps on 1st October 1920. Although he was entitled to keep his AIF rank of Major as an honorary rank, his substantive rank - and pay grade- was still Lieutenant. Promotion was painfully slow. He was promoted to Captain and Brevet Major on 1st March 1923, but was not promoted to substantive rank of Major until 1st March 1935.

He attended the Royal Military Academy, Woolich from 1920 to 1923. On returning to Australia he became an inspecting ordnance officer at the 2nd Military District. While here, Berryman enrolled in a Bachelor of Science program at the University of Sydney. On 30th November 1925 he married Muriel Whipp and the couple were to later have a daughter and a son. Muriel Berryman was also over the years a tower of strength in her support of her husband and in her personal initiatives which brought many benefits to Army wives, war widows and others. In 1972 Lady Berryman was appointed CBE for her work with charities.

Berryman discontinued his university studies to prepare for the entrance examination for Staff College, Camberley. Eighteen Australian Army officers sat the exam that year, but only Berryman and one other officer passed. Only two Australian officers were accepted into Staff College each year, so Berryman's attendance from 1926 to 1928 marked him out as one of the Australian Army's rising talents. It also allowed him to forge useful contacts with the British Army. Berryman later recalled, "The advantage of this was that in war we had the same doctrine of tactics and administration, which was essential if we had to work together. More than that, the officers who had to carry out their duties in cooperation knew each other personally”. After graduation he was posted to the High Commission of Australia, London, from 1929 to 1932.

After nearly twenty years as a major, Berryman was promoted to brevet lieutenant colonel on 12 May 1935. Promotion to substantive rank, which carried the rank's pay as well as status, occurred on 1 July 1938, when he became Assistant Director of Military Operations at Army Headquarters. From December 1938 to April 1940 he was General Staff Officer Grade 1 (GSO1) of the 3rd Division. The slow rate of promotion of regular officers in the inter-war years fostered a sense of injustice and frustration among officers with good war records who found themselves outranked by Militia officers who had enjoyed faster promotion.

The final straw for many regular officers was Prime Minister Robert Menzies' announcement that all commands in the Second AIF would go to Militia officers, which Berryman considered "a damn insult to the professional soldier, calculated to split the Army down the centre. We were to be the hewers of wood and the drawers of water. We, the only people who really knew the job, were to assist these Militia fellows."

Berryman joined the Second AIF on 4 April 1940 with the rank of full Colonel, receiving the AIF serial number of VX20308, and became General Staff Officer Grade 1 (GSO1) of Major General Iven Mackay's 6th Division, in succession to Sydney Rowell who stepped up to become chief of staff of I Corps. Berryman soon established a good working relationship with Mackay. Despite the friction between Militia and Staff Corps officers, Berryman chose to assess officers on performance. This meant that while Berryman viewed some Militia officers, like Brigadier Stanley Savige of the 17th Infantry Brigade, with disdain, he maintained good relations with others. There were also personal and professional rivalries with other Staff Corps officers, such as Alan Vasey. Yet even those who disliked Berryman personally for his lack of patience and tact and referred to him as "Berry the Bastard" respected his abilities as a staff officer.

Mackay and Berryman were determined that the Battle of Bardia would not be a repeat of the disastrous landing at Anzac Cove in 1915. Berryman's talent for operational staff work came to the fore. From studies of aerial photographs, he selected a spot for the attack where the terrain was most favorable. His plan provided for the coordination of infantry, armour and artillery. While at times, he proved secretive and hard to deal with, during the battle his forceful personality provided a good foil to the sometimes indecisive Mackay. Later that month Berryman planned the equally successful Battle of Tobruk. For his services in this campaign, he was made a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE).

In January 1941, Berryman became Commander, Royal Artillery, in Arthur "Tubby" Allen's 7th Division, and was promoted to Brigadier. During the Syria-Lebanon campaign, Berryman demonstrated that he was a thrusting commander who led from the front and repeatedly demonstrated his coolness under fire. When his headquarters came under shell fire for the first time, Berryman sat calmly eating his breakfast "among the flying brick dust and bursting shells", simply telling the men to shut the door, "so they can eat breakfast without being covered in dust".

During the Vichy French counterattack, Berryman was given command of the Australian forces in the centre of the position around Merdjayoun. This scratch force became known as "Berryforce". His mission was to check the enemy advance in the Merdjayoun area. Berryman decided that the best way to do this would be to recapture Merdjayoun. This presented considerable difficulty, for although his force contained two infantry battalions, the 2/25th and 2/33rd, and a pioneer battalion, the 2/2nd, his headquarters was not equipped to control a battle in the manner of an infantry brigade, as it lacked appropriate staff and communications. Moreover, while he was supported by mechanised cavalry and 22 artillery pieces, the opposing French forces had tanks.

For the next two weeks, the outnumbered Berryforce attempted to retake the strategically important town in the Battle of Merdjayoun. His first attempt was a failure. After carrying out a personal reconnaissance on 18 June, Berryman tried again. This time his attack was halted by staunch defence by the French Foreign Legion and tanks. Berryman then tried a different approach. Instead of attempting to capture the town, he seized high ground overlooking the French supply lines. Faced with being cut off, the French withdrew from the town. Berryforce was then dissolved and Berryman returned to his role as commander of the 7th Division Artillery.

The 7th Division was now concentrated in the coastal sector. Berryman clashed with Brigadier Jack Stevens of the 21st Infantry Brigade over the siting of Berryman's artillery observation posts, which were forward of the infantry's front lines. Berryman wanted Stevens' positions advanced so as to obtain effective observation of the enemy's lines for Berryman's gunners. Stevens refused, hampering Berryman's efforts to support him in the Battle of Damour. Despite this, Berryman implemented an effective artillery plan. In the final stage of the battle, Berryman, without authority, ordered Lieutenant Colonel Denzil MacArthur-Onslow of the 2/6th Cavalry Regiment to pursue the retreating French forces, but was overruled by Savige and Allen. For his part in the campaign, Berryman received a third Mention in Despatches.

On 3rd August 1941, Berryman became Brigadier, General Staff (Chief of Staff) of I Corps under Lieutenant General John Lavarack, again in succession to Rowell, who became Deputy Chief of the General Staff (DCGS). Berryman arrived in Jakarta by air with the advanced party of the I Corps headquarters staff on 26th January 1942 to plan its defence. Berryman reconnoitered Java and prepared an appreciation of the situation. Berryman also attempted to find out as much as possible about Japanese tactics through interviewing Colonel Ian MacAlister Stewart. This information found its way into papers circulated throughout the Army in Australia. It soon became apparent that the situation was hopeless and any troops committed to the defence of Java would be lost.

Berryman returned to Australia, where he was promoted to Major General on 6th April 1942, when he became Major General, General Staff (Chief of Staff) of Lavarack's First Army. On 14th September 1942, Berryman became DCGS under the Commander in Chief, General Sir Thomas Blamey, in succession to Vasey. When New Guinea Force split into a rear headquarters under Blamey and an advanced headquarters under Lieutenant General Edmund Herring, so the latter could go forward to direct the Battle of Buna-Gona, Blamey brought Berryman up from Advanced LHQ in Brisbane to simultaneously act as chief of staff of New Guinea Force from 11 December 1942. Berryman formed a very close professional and personal relationship with Blamey, and henceforth Berryman would be Blamey's chief of staff and head of operational planning, which made him "one of the most important officers in the Australian Army in its struggle against the Japanese.

Blamey and Berryman remained close for the rest of the war, and Blamey came to rely heavily on Berryman for advice. It was Berryman who was sent to Wau to investigate the difficulties that Savige was having, and it was Berryman who exonerated Savige. "I reported the situation [to Blamey and Herring]," Berryman record in his diary, "and said Savige had done well and we had misjudged him." Berryman was intimately involved with the planning of the Salamaua-Lae campaign, working closely with Brigadier General Stephen J. Chamberlin at General Douglas MacArthur's General Headquarters (GHQ) in Brisbane. Berryman established good working relations with the Americans, even though their staff practices were quite different to those of the Australian Army.

Berryman understood the Americans and they understood him; he had a knack of avoiding friction without sacrificing Australian dignity or interests. His achievements in keeping the peace were of no mean order in light of America's preponderant contribution to the overall forces under MacArthur's command. It was a time when a careless word or a thoughtless gesture could have upset the delicate balance of the Australian-American partnership.

Berryman was also involved in the plan's execution, once more becoming chief of staff at New Guinea Force under Blamey in August 1943. Berryman was frustrated at the failure of Vasey's 7th Division to destroy the Japanese retreating from Lae, and personally annoyed by the way that Vasey forwarded compliments to Major General Ennis Whitehead while leaving any complaints about air support to be taken up by Berryman. Berryman was next involved with the planning for the landing at Finschhafen, brokering a compromise landing plan between Rear Admiral Daniel E. Barbey and Lieutenant General Sir Edmund Herring. When Berryman discovered that the United States Seventh Fleet did not intend to reinforce the 9th Division he immediately went to Blamey, who took the matter up with MacArthur. However, it was Berryman who brokered a compromise deal with Vice Admiral Arthur S. Carpender to reinforce Finschhafen with a battalion in transport destroyers (APDs).

On 7th November 1943, Berryman became acting commander of II Corps, a post which became permanent on 20th January 1944, superseding Vasey, whose 7th Division was diplomatically placed directly under Lieutenant General Sir Leslie Morshead's New Guinea Force. II Corps was left with the 5th and 9th Divisions. Berryman was promoted to Lieutenant General on 20th January 1944. As in Syria, Berryman proved a hard-driving commander. In December 1943, II Corps broke out of the position around Finschhafen and began a pursuit along the coast. Whenever the Japanese Army attempted to make a stand, Berryman attacked with 25-pounder artillery barrages and Matilda tanks. Berryman was aware that seasonal changes were making the surf rougher and making it ever harder to operate the US Army landing craft (LCMs) and Australian Army amphibious trucks (DUKWs) that he depended for the logistical support of his troops, but he realised that the Japanese Army's supply difficulties were greater than his own, and he gambled that if he pushed hard enough the Japanese would be unable to regroup and organise a successful defence.

In the first phase of the Battle of Sio, the advance from Finschhafen to Sio, 3,099 Japanese dead were counted and 38 prisoners taken, at a cost of 8 Australians killed and 48 wounded. In the 5th Division's subsequent drive from Sio to link up with the US 32nd Infantry Division at Saidor, 734 Japanese were killed and 1,775 found dead, while 48 prisoners were taken. Australian casualties came to 4 killed and 6 wounded. MacArthur considered Berryman's performance "quite brilliant". For his part in the campaign, Berryman was made a Companion of the Order of the Bath (CB) on 8th March 1945.

II Corps was renumbered I Corps on 13th April 1944 and returned to Australia, where Blamey gave Berryman his next assignment. In preparation for the Philippines Campaign, General MacArthur moved the advanced element of GHQ to Hollandia in Dutch West Papua, where it opened in late August 1944. To maintain contact with GHQ, Blamey formed a new headquarters, Forward Echelon LHQ, which opened at Hollandia on 7th September under Berryman, who became Blamey's personal representative at GHQ. Forward Echelon LHQ subsequently moved with GHQ to Leyte in February 1945 and Manila in April 1945. Berryman's role was to "safeguard Australian interests" at GHQ, but he also defended GHQ against criticism from the Australian Army. As well as liaising with GHQ, Forward Echelon LHQ became responsible for planning operations involving Australian troops. It worked on plans for operations on Luzon and Mindanao before it was finally decided that Borneo would be the Australian Army's next objective. In all of this Berryman kept in close contact with Blamey, and the two were Australian Army representatives at the Japanese surrender in Tokyo Bay in September 1945.[24] For his services in the final campaigns, Berryman received a fourth and final Mention in Despatches on 6th March 1947.

| |

|

|

In an article in The Bulletin published in 1961, it was stated that Berryman had “a hard streak of inflexible purpose, an eye which will tolerate no slackness and the ability, in a few chosen words, to leave everyone who tried to come over him in no doubt about his proper place and future action”.

After the war, Berryman took charge of Eastern Command, an appointment he held from March 1946 until his retirement at age 60 in April 1954. Berryman became known for his involvement in charitable organisations such as the War Widows Association, and in fact was a founder of the War Widows Guild. He was also head of the Remembrance Drive Project and a director on numerous public companies. For this and his commitment to beautifying the Army barracks, Berryman became colloquially known in the Army as "Frank the Florist".

In June 1949, the country was rocked by the 1949 Australian coal strike. The strike began when stocks of coal were already low, especially in New South Wales, and rationing was introduced. Prime Minister Ben Chifley turned to the Army to get the troops to mine coal. This became possible when the transport unions agreed to transport coal that was mined. Responsibility for planning and organising the effort fell to Berryman. Soldiers began mining at Muswellbrook and Lithgow on 1st August, and by 15 August, when the strike ended, some 4,000 soldiers and airmen were employed. They continued work until production was fully restored.

Berryman hoped to become Chief of the General Staff in succession to Lieutenant General Vernon Sturdee but he was seen as a "Blamey man" by Chifley and his Labor government colleagues, who disliked the former Commander-in-Chief. The job was instead given to Rowell. The United States government awarded Berryman the Medal of Freedom with Silver Palm in 1948. Following the change of government in 1949, Berryman lobbied Sir Eric Harrison, the Liberal Minister for Defence Production, for the job on the retirement of Rowell in 1954, but he was now considered too old for the job.

Berryman became the Director General of the Royal Tour of Queen Elizabeth II in 1954, for which he was made a Knight Commander of the Royal Victorian Order (KCVO). He was Chief Executive Officer of the Royal Agricultural Society of New South Wales from 1954 to 1961. He died on 28th May 1981 at Rose Bay, New South Wales, and was cremated with full military honours. At the time of his funeral the Ambassador for Lebanon, Raymond Heneine, wrote in the Canberra Times: "The inhabitants of Jezzine will never forget General Berryman, who liberated their town from the forces of the Vichy French in collaboration with the Italian and German forces. He was for them not only a great general but also a great benefactor who provided them with food supplies and medical care. In fact he was the example of humanitarianism".

Berryman and his wife had put their roots down in Sydney and they lived in Victoria Barracks. General Dunstan observed that “(Victoria Barracks) is today an oasis in the city and due in no small measure to Sir Frank Berryman who transformed the drab barracks of the war era and laid the foundations of the grounds and gardens which are there today”. Dunstan went on to say “the official history refers to the ‘ever active Berryman’. It is this quality which comes through so strongly in our recollection of him. Senior Commanders when reporting on him as a young officer, refer to many other qualities: for example, to ‘professional attainments of the highest order’; that ‘in full measure he possesses all the requisite personal qualities’; that ‘his personal characteristics are above reproach’. If now somewhat old fashioned in expression these statements are clear, concise and perceptive. Acknowledgements:

- Wikipedia

- Eulogy by Lieutenant General Sir Donald Dunstan, AC, KBE, CB published in Australian Gunner November 81 Edition.

Berryman, Sir Frank Horton (1894 – 1981) by A. J, Hill published in Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 17, (MUP), 2007. |