|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Have a Question / Feedback ? | Submit- only questions about this website will be answered | Search Our Site |

|

| HISTORY OF EMPLOYMENT OF AUSTRALIAN ARTILLERY |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Should you have a question, wish to submit additional information or identify an error please use the 'Have a Question? Provide Feedback? option within the menu bar above. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Images used herein are from the Australian War Memorial, or Defence Image Gallery” | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Prelude

The Boer War experience revealed shortcomings in early breech-loading, non-recuperating guns. Subsequently, the 18-pounder Quick-Fire guns and equivalents were introduced into service afterwards, along with heavier calibre howitzers designed for high angle, destruction and neutralisation – though the latter were in short supply and not standardised. The 18-pounder design still reflected the expected mobility to support infantry and cavalry columns of the 19th century, and made extensive use of shrapnel shells and firing in a direct fie mode. Gallipoli 1915

The Gallipoli campaign witnessed Australia’s first wholesale involvement in Industrial-era warfare and all its lethality, complexity and consumption, unmatched in its scale and national commitment to that date.

Sinai-Palestine 1915-1918

The tenets of mobile warfare were retained in Palestine, as the theatre's terrain and scale afforded manoeuvre the advantage. Austere logistic lines of supply for both sides saw relatively low intensities of artillery expenditure predominate.

While no Australian artillery deployed, British guns supported Australian Light Horse and other Desert Mounted Corps formations in direct and indirect fire roles, in a fluid mix of rapid advances and the reduction of Ottoman defended positions. The campaign’s tempo and lower strategic priority moderated adoption of contemporary artillery technological and tactical evolutions occurring on the Western Front, such as counter-battery1 techniques, and the pursuit of predicted (i.e. calculated rather than adjusted) fire.

Western Front – the modern gunnery problem 1916-1918

On its arrival on the Western Front in 1916, the Australian Imperial Force and the Australian Field Artillery (AFA)2 were confronted by a campaign where defence had a considerable advantage over the attack, and manoeuvre had given way to static positions and unprecedented attrition.

The employment of anti-aircraft artillery spread rapidly as the war progressed. Heavy and light machineguns and field artillery were originally re-purposed, but soon replaced by purpose-built, quick-fire guns such as the 3-inch, and the 1-pounder ‘pom-pom’. Immense mathematical and physics challenges in target acquisition, range finding and airburst fuse setting were rapidly confronted. Though initially not coordinated beyond local point defence, Allied and German anti-aircraft artillery nevertheless accounted for many hundreds of aircraft kills, including – famously – the ‘Red Baron’, by a 53rd Battery, Australian Field Artillery gunner.

While aerial observation from balloons had occurred for decades, the advent of fixed wing flight and improvements in aerial photography permitted huge advances in the speed of intelligence dissemination and application, including, for artillery, predicted fire for both assault and defence. Gridded photomaps shared aloft and at the gun-line now permitted rapid target indication and engagement. Airborne wireless radio introduced in the final months of 1917 – employed notably later in mid-1918 at Le Hamel – permitted real-time artillery adjustment to barrages. Fireplan barrages evolved from simple, fixed arrangements to creeping barrages that moved in front of advancing troops, standing barrages that neutralised whole enemy trench lines, and lifting barrages which were standing barrages that moved wholly to subsequent objectives and cut-offs. Defensive fireplans included predicted-fire Support or Suppression (SOS) missions that engaged likely enemy approaches, while box barrages were fired around advancing troops on new-won objectives to counter enemy penetration.

Other standard Australian Field Artillery fire missions included registration as well as ‘search’ and ‘sweep’ missions that were employed across areas to harass forward troops or unmask enemy guns, while heavier calibre howitzers conducted harassment & interdiction missions against depth targets, using predicted fire generated from aerial reconnaissance.

The increasing complexity of artillery tactics and functions led to commensurate augmentation of the staff of divisional-level General Officers Commanding Royal Artillery (GOCRA)3. Similarly, the growing incidence of corps-level artillery fireplanning in support of corps- and higher-level deliberate operations saw the creation of corps-level artillery commanders across British and subsequently Dominion forces, with steadily increasing authority to allot, coordinate and orchestrate the fireplanning and employment of massed artillery. This included Brig.-Gen Coxen as the first Australian artillery commander of the newly formed Australian Corps from November 1917.

By the mid-1916, artillery command and control – the allocation and employment of firepower assets at all levels – had evolved to permit strong, highly centralised command of guns, primarily to support the destructive massed fireplans of 1916 and 1917. By the War’s end, artillery command and control had further developed to allow equally, the decentralisation of artillery control; permitting commanders to more flexibly allot and guarantee fire support along the front. Rapid improvements in communications, fixation, orientation and ballistic correction facilitated the development of artillery support tasking, which in turn unleashed an unprecedented capacity for artillery to switch and move fires across the front, in greater concert with manoeuvre forces.

Despite the immense efforts given to perfecting artillery indirect fire, artillery in direct fire roles was still essential for the reduction and destruction of obstacles in the attack – such as by 6th Battery, Australian Field Artillery at Pozières – or later, as prototype anti-tank guns, successfully employed first by German defenders at Bullecourt, and adopted later by both sides. Both HE and shrapnel shells were employed – the latter effective in direct fire, where the fuse could be set accurately.

1 Alternately termed counter-bombardment during World War One.

2 The Australian Field Artillery comprised the artillery elements of the Australian Imperial Force, and was drawn from pre-war RAA, Royal Australian Field rtillery (RAFA) and Royal Australian Garrison Artillery (RAGA) personnel, volunteer Militia artillerymen, and new recruits.

3 Alternately titled Brigadier-General Royal Artillery from May-Dec 1916.

4 Today's equivalent of gun regiments. The 1930s saw widespread downsizing across the Australian Military Forces, including the demise of corps-level artillery commanders, and the diminishing of divisional-level Commander Royal Artillery functions. Confronting the task of defending a continent with a depleted force based on the rhetoric of the Singapore Strategy, the Chief of the General Staff John Lavarack convinced the Government to invest in motorisation and re-equipping of its modest land forces, including artillery.

Tobruk, Greece and Crete 1941

Syria-Lebanon 1941

This Australian-led campaign to clear dogged Vichy French resistance witnessed the extensive, innovative employment of Australian and British Dominion field artillery in the advance and attack, fixing Vichy defenders while Allied infantry and light armour manoeuvred to outflank or bypass. As well as standard missions, single guns and artillery sections were continually used forward in anti-tank and direct-fire tasks. Though only two Australian field artillery regiments were in action during the Syrian campaign, Australian artillery fired almost 15,000 rounds. Australian Continental Defence 1939-45

North Africa (after Tobruk) 1942

The 9th Australian Division’s artillery assets were an integral part of the British 8th Army during the later North African campaign, which was characterised by employment of many artillery tactics and techniques from World War One: regular use of counter-battery fires, detailed and concentrated fireplans in support of mass attacks, and heavy use of dedicated aerial observation. Australian Army Air Liaison Officers7 were also heavily employed in coordinating the air-ground battle.

PNG and Pacific Islands 1942-45

As the campaign progressed, naval gunfire and Close Air Support became increasingly available – the latter founded upon the advent and growth of the pivotal Army Air Liaison Officers’ function. The clearances of the last Japanese forces from the northern New Guinea coast and subsequent landings in Borneo witnessed the Australian Army’s emergence as a dedicated jungle fighting force, developing a far closer integration of artillery and fire support coordination with manoeuvre units at brigade level. This was a departure from the level of command and scale of employment seen in Europe, Middle East and Africa – and, indeed, on the Eastern Front. Nevertheless, by the end of the War, the Royal Australian Artillery had raised in excess of 70 regiments of field, medium, anti-tank, anti-aircraft and survey artillery.

5 Australian artillery Gunners operated fully functional captured Italian and recaptured British air defence, anti-tank and field artillery pieces, alongside Australian infantry using partly functional captured Italian guns known as the ‘Bush Artillery’.

6 More latterly referred to as combined arms.

7 The precursore to modern-day Ground Liaison Officers (GLOs) Korea 1950 - 53

Pentropic reorganisation 1960-65

Australia nonetheless remained focussed on regional specialisation, and soon after, adopted the Pentropic organisation, wherein Australia’s reorganised two divisions were intended to be air-portable, capable of fighting in a limited war and of conducting dispersed anti-guerrilla operations. For the RAA, this meant the introduction of 105mm L5 Pack Howitzers and rugged, air-portable M2A2 guns, and development of weapon-locating and SAM capabilities. At divisional level, heavier calibre 5.5in guns were introduced, though the guided missiles also proposed never eventuated.

Whereas once divisional-level, then brigade-level was the principal echelon of tactical action, now it had become the Pentropic 'battle group'. Despite a strengthened divisional artillery group, the Pentropic concept’s organisational decentralisation accelerated a trend away from proficiency in formation-level joint fires coordination and concentration, practiced in the previous world wars.

8 This development led to change in nomenclature to Air Defence (AD), then progressively Ground-Based Air Defence (GBAD), to distinguish from the corresponding air power role. Despite discontinuing the abortive Pentropic experiment, Australia’s foreign and defence policy of Forward Defence prompted expeditionary intervention operations across South-East Asia. Counter-insurgency operations in tropical terrain prevailed, with an emphasis on dominating ground through aggressive patrolling, based out of and supported from defensible firebases. Malaya 1950-63 and Malaysian-Indonesian Confrontation 1963-66

South Vietnam 1962-72

With the commitment to Vietnam came a change in threat to a mix of irregular and regular force adversaries. Interoperability with US forces became vital, and scale and intensity of combat increased markedly, though changes in Australian artillery employment occurred more slowly. Vietnam saw the evolution of company bases into battalion group size Fire Support Patrol Bases, adding armoured elements to the infantry forces.9 This concept would develop further through the employment of Forward Operating Bases during subsequent coalition operations in Iraq and Afghanistan.

9 Also known as Fire Support Bases or Firebases.

10 More recently termed simply Air Interdiction. Close air support refers to support to fighting elements in combat, while air interdiction refers to engagement of target deeper in enemy territory. Post-Vietnam 1973 - 1999

Withdrawal from Vietnam saw force reductions and further batteries disbanded, and an Army reorganisation re-focussed towards a Cold War conventional threat. The re-focus witnessed a short-lived recognisance of the importance of coordination of artillery at the divisional level that was reflected at least in Australian artillery doctrine and training, if not in its organisation.

As the spectre of war with Warsaw Pact forces evaporated, the 1990s saw the onset of the Defence of Australia doctrine, anticipating widespread low-incidence, though lethal, threats. The Army in the 21st Century (A21) Trials proposed highly decentralised command of fire support, and artillery integrated as organic assets into motorised infantry. In response to the prevailing Defence of Australia doctrine, a concept of ‘continental’ force projection similar to that exhorted between the Wars was attempted, as a desperate recourse to maintain a nucleus of modern levels of firepower and manoeuvre, in the face of dwindling defence expenditure.

Improvements in fire control computerisation allowed the ability to disperse firing locations, yet accurately concentrate fire, and supported the introduction of artillery precision-guided munitions. Advent of precision-guided munitions indisputably re-introduced destruction as a primary artillery mission.

The A21's 6th Motorised Battalion Group construct trialled an organic armoured cavalry reconnaissance troop; guns of both light and medium calibre distributed in section-level positions; forward observer parties; organic weapon-locating, meteorological and survey assets; and the inception of a battalion-level All-Sources Cell. Importantly, the latter fused organic artillery and cavalry intelligence collection, but also imagery from the battalion’s primitive unmanned aerial vehicles, thermal imagery and ground surveillance radars in Reconnaissance/ Surveillance Company. While locally potent and well supplied in intelligence, the A21 concept’s command structure lacked the flexibility to aggregate forces, and to coordinate its artillery firepower in support of higher-level, high intensity operations.

Meanwhile in the late 1990s, Headquarters 1st Task Force was experimenting with Joint Offensive Support Coordination Centre structures, building on the functions and capability of the predecessor Fire Support Coordination Centre organisation. Timely fusion of intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR), and coordination of lethal and non-lethal effects entered Australian Army developing doctrine, and with it the re-defining of the employment of artillery at formation level.

Consequently, Australian land force doctrine developed the option of employing artillery elements in civil-military cooperation roles, particularly in evacuation scenarios, exploiting the Gunners’ intrinsic characteristics as well-equipped combat soldiers, organised for command, liaison & observation tasks in all threat settings. All recent Royal Australian Artillery employment reflects an ongoing prominence of artillery command, liaison, observation, communications and targeting functions. Royal Australian Artillery staff and commanders have provided individual or staff cell contributions to all Australian deployed headquarters, and individual third-country embedded staff into larger coalition headquarters in all active theatres – Timor-Leste, Iraq, Afghanistan and the wider Middle East. The application of artillery principles learned in lethal fires engagements were redeveloped to provide clear and effective appreciations of employment of non-lethal effects such as Information Operations and public information, and even the calculated apportionment of development assistance. Timor 1999-2012

In support to United Nations peacekeeping operations in Timor, the scale of the mission, prevailing low threat and low lethality induced the re-role of artillery sub-units into infantry and other non-artillery roles, reprising similar Royal Australian Artillery employment in earlier conflicts. Initially however, while the threat was uncertain, options were retained for the deployment of field artillery to provide close support from firebases in familiar counter-insurgency roles, operating in austere, disaggregated and tropical settings. Meanwhile, Royal Australian Artillery command, liaison and observation groups performed important civil-military roles, coordinating with humanitarian and development assistance. Iraq 2003-2011

Afghanistan 2005-2014

After the initial Special Operations-led commitments in 2001-2, Australian military intervention into Afghanistan in the Regional Command-South area of operations increased and diversified from 2005, deploying into a moderate threat setting of sporadic indirect fire, but escalating ground threat in terms of direct fire and improvised explosive devices. Although Australia did not deploy organic artillery fire assets with successive reconstruction and mentoring units, the provision of supporting Joint Offensive Support Teams and a Joint Fires & Effects Coordination Cell12 was imperative to Australian targeting and access to reinforcing coalition fires and effects. Interoperability with North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO), International Stabilisation Assistance Force (ISAF) and US forces became essential; and Australian Special Operations and manoeuvre elements in both Uruzgan province and beyond relied on US and NATO artillery, mortar, attack aviation and close air support throughout the campaign.

Separately, a troop of Royal Australian Artillery field artillery was also embedded with British Royal Artillery/Royal Horse Artillery field batteries in support of British operations in neighbouring Helmand province, where the ground and indirect threat was markedly higher. The tempo and intensity of artillery fire – both indirectly supporting Coalition manoeuvre forces, and directly in local defence of the troop’s own firebases – were considerable, regularly requiring significant augmentation by joint fires from helicopter attack aviation and close air support.

Within the International Stabilisation Assistance Force mentoring mission, the Royal Australian Artillery deployed several joint fires & effects training teams, including personnel within the Army’s combat support Observation, Mentoring and Liaison Teams, training individual Afghan National Army field artillery batteries to combat readiness. Additionally, the Artillery Training Team – Kabul was responsible for wider artillery training within the Afghan National Army’s Training Command, while other Royal Australian Artillery training elements were embedded within the Afghan National Army Officer Academy and elsewhere.

11 JOST replaced the more generic and historic term of Forward Observer party, reflecting a regularly wider role of application of and access to non-artillery fire support. The term JOST was itself later replaced to the simpler Joint Fires Team (JFT).

12 The Joint Fires & Effects Coordination Cell term superseded the Joint Offensive Support Coordination Centre.

13 The term Forward Observer was altered to Joint Fires Observer to reflect the growth in accessing joint fires.

14 The term Forward Air Controller was altered to Joint Terminal Attack Controller to reflect the ability to terminally control all forms of joint fires. The contemporary joint fires battlespace continues to evolve, presenting new considerations for modern artillery employment. Developments in long range precision surface fires and multi-domain fires exploiting the electro-magnetic spectrum continue, matched by a revitalisation of ground-based air and missile defence, and the enduring importance of joint fires and effects planning, coordination and advice. Iraq 2016-18

Recent Coalition operations in Iraq from 2016 have faced considerably increased threat in terms of scale, intensity and lethality from Islamic State militants. In providing modern coalition joint fires and enablers to the beleaguered Iraqi Security Forces, Operation Inherent Resolve forces have provided highly effective intelligence, surveillance & reconnaissance and targeting through coalition Joint Terminal Attack Controllers and artillery observer mentors. These elements coordinated overwhelming quantities of lethal and pervasive joint fires – both precision-guided munitions as well as conventional munitions – delivered from US and NATO field artillery guns, rockets and mortars, in the form of long-range precision fires and artillery raids from prepared firebases.

Meanwhile, coalition joint fires and effects mentors aided Iraqi Army artillery in providing close support to Iraqi manoeuvre forces in the advance and attack against Islamic State forces. Coalition Strike Cells coordinated all coalition joint fires on behalf of Iraqi forces, as the Iraqis prepared to develop their own fledgling theatre-level joint fires coordination. Within Coalition headquarters at component and combined joint task force levels, Royal Australian Artillery personnel were embedded as part of targeting and joint fires and effects coordination. Today’s joint fires battlespace

Contemporary artillery employment characteristics include: full coalition integration; inherent expeditionary capability; high-technology, high-lethality adversaries; global political interest in tactical outcomes; and full spectrum conflict short of nuclear exchange. Modern joint fires now comprise surface-surface missiles and rockets, ‘tube’ artillery, mortars, naval gunfire, attack aviation, and airborne strike (close air support and air interdiction) from manned aircraft and unmanned aerial vehicles. Coalition interoperability in coordination offers unprecedented joint fires access.

Artillery command, liaison & observation groups15 still provide the joint fires 'brokerage' to manoeuvre arm commanders. Provision of Joint Terminal Attack Controllers and Joint Fires Observers remain integral conduits for vital reach-back & coordination for joint fires and effects – including non-lethal effects such as information operations, electronic warfare and even cyber – at increasingly lower tactical levels.

Dramatic improvements in intelligence fusion in theatres with unchallenged airspace have permitted uncontested, high quality targeting of irregular adversaries for neutralisation or destruction. However, detection is often possible when discrimination is not, and lethal engagement remains constrained under rules of engagement. Contemporary conflict between other belligerents – such as in Ukraine – demonstrate that target development is less simple against peer adversaries in hotly contested domains, especially air and the electro-magnetic spectrum.

Theatre-level precision for location and orientation via satellite geo-location is now prevalent, but the growing threat of electro-magnetic signal interference is creating a fast-growing need for autonomous geo-location & orientation systems. Accurate meteorological data remains essential, and though increasingly provided automatically, is still difficult to disseminate time-sensitively.

While some Royal Australian Artillery surveillance & target acquisition systems including ground sensors, surveillance radars and acoustic sensing have not recently deployed, these systems have all been employed by coalition partners and other belligerents in recent conflicts. Further systemic refinements to counter-rocket, artillery & mortar systems will fully integrate the initiation of multiple responses – force protection measures and launch of intelligence, surveillance & reconnaissance assets, as well as lethal counter-bombardment. This tactical approach reflects irregular adversary use of indiscriminate, disparate indirect fire from highly mobile, low-detectability platforms in several recent conflicts.

The Air Observation Post is now embodied in the Royal Australian Artillery’s own, and other airborne intelligence, surveillance & reconnaissance capability. Unmanned aerial vehicles feed product directly to coalition fires strike cells. Ubiquitous, high trust communications networks permit commensurate levels of centralised fusion and allocation of scarce joint fires assets, across vast areas of operation.

Anti-Aircraft Artillery Defence has evolved into Ground-based Air & Missile Defence, capable of being fully synchronised into integrated air defence systems at multiple levels of command and control. The projected re-introduction of standoff ground-based air & missile defence in the Australian Defence Force will complement the Royal Australian Artillery’s legacy low-level air defence capability. Recent operations with no or minimal air threat has lowered wider military perceptions of the requirement for such a capability. However, the intensifying threat from potential enemy unmanned aerial vehicles, and maturing technological solutions to provide effective counter-rocket, artillery & mortar systems is correcting this misperception.

The value of artillery to coastal defence is again being recognised. The proposed acquisition of long-range surface-to-surface rocket systems primarily for land-based deep fires also has utility in anti-access anti-denial in the maritime environment. When linked with other advances in the Royal Australian Artillery’s acquisition, lethality, range and operational and tactical mobility, these systems will provide highly effective standoff artillery in the maritime environment. The Royal Australian Artillery today

Currently, the Royal Australian Artillery comprises seven units and a number of smaller, enabling force elements. There are three gun regiments equipped with 155mm towed howitzers, each regiment supporting a combat brigade; one regiment responsible to provide surveillance and target acquisition primarily through Unmanned Aerial Systems;16 and one regiment equipped with missile systems and extended-range radars responsible to provide Army’s air defence capability. The latter two regiments are force-level assets, grouped as part of 6th Combat Support Brigade. Within the 2nd Division, the Royal Australian Artillery’s Reserve regiment equipped with 81mm mortars and smaller unmanned aerial vehicles provides joint fires and effects command & control, joint fires observers, and close fire support to the various 2nd Division battlegroups. The School of Artillery continues to conduct artillery and joint fires and effects training for all Royal Australian Artillery trades, as well as individual training for infantry mortars.

Along with a number of smaller individual elements embedded across the Australian Defence Force, the Royal Australian Artillery collectively provides the land domain element of the Australian Defence Force’s joint fires and effects capability system. Several key changes in progress, or due to commence in the near future, will further enhance and evolve these capabilities. The Royal Australian Artillery is currently well placed to incorporate these changes, and adapt effectively to the future battlespace and warfighting environment.

15Also known as Tactical or Tac Groups.

16Unmanned Aerial System (UAS) describes the entire capability system (airframes, ground control station, Command & Control nodes, observation and advice elements), whereas the term UAV describes the airframes specifically. Tenets of artillery employment

The history of Australian artillery employment reveals a highly varied application of offensive support and coordination. Moreover, it demonstrates that all branches of artillery – surface-surface field artillery, STA, GBAMD, airspace coordination, targeting and strike coordination – and accompanying artillery advice to manoeuvre commanders are all still relevant contributors to joint battlespace functions. Conventional artillery remains integral to contemporary conflict in all its forms, while the unique character of each conflict and national strategic commitment drives artillery’s varied manifestation, employment and prominence in each battlespace.

The history of Australian artillery employment reveals a highly varied application of offensive support and coordination. Moreover, it demonstrates that all branches of artillery – surface-surface field artillery, surveillance & target acquisition, ground-based air & missile defence, airspace coordination, targeting and strike coordination – and accompanying artillery advice to manoeuvre commanders are all still relevant contributors to joint battlespace functions. Conventional artillery remains integral to contemporary conflict in all its forms, while the unique character of each conflict and national strategic commitment drives artillery’s varied manifestation, employment and prominence in each battlespace. The ‘gunnery problem’ dilemmas arising from technological deficiencies during World War One are now able to be resolved, founded on ongoing application of underlying principles of ballistics, kinetics and chemistry. Nonetheless, several aspects of artillery employment remain consistent.

Other aspects of joint fires coordination have merely evolved in their sophistication of employment.

The employment of artillery remains a fundamental component in the application of land forces, and in the combining of firepower with manoeuvre. Artillery commanders at all levels must be highly flexible and readily adaptable in its employment, and anticipate artillery’s latent potential for widespread application in all operational theatres, with commensurate rates of expenditure.

Editor's Note: * This history was originally written by Lieutenant Colonel NH Floyd in conjunction with the RAA’s Regimental History Committee, for Combined Arms Training Centre, as an Annex to the forthcoming edition of LWD 3-4-1 Employment of Artillery, and designed to provide an informative historical context for artillery employment throughout Australian military history. It was originally published in Cannonball No. 97 Winter 2020. The content here has been revised and updated in 2021.

* The text will form the basis for a larger, more detailed work currently under development, on the ‘Essential History of Australian Artillery 1871-2021’. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

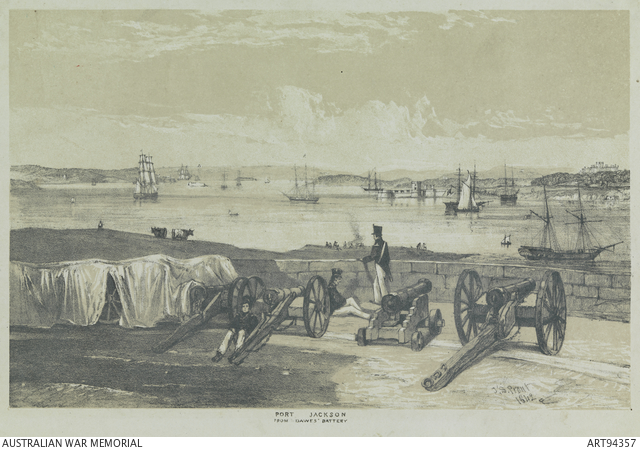

Port Jackson, from Dawes' Battery

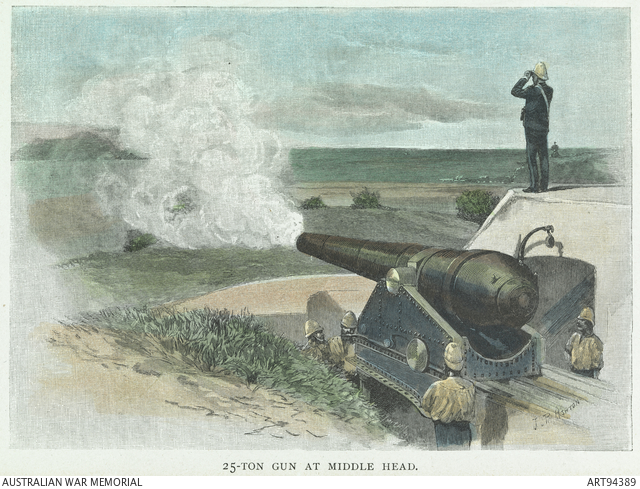

25 - Ton gun at Middle Head

'A' Battery Field Artillery, New South Wales

The last shot at Colenso

Australian Army soldiers from 8th/12th Regiment, Royal Australian Artillery, fire an M777 lightweight towed howitzer

during

Exercise Predator's Gallop at Woomera test range, South Australia, on 28 February 2016.

The AAI Shadow 200 tactical unmanned aerial system is recovered post mission at Multi National Base - Tarin Kot.

7th Battalion Royal Australian Regiment Task Group Other Government Agency Platoon One, Joint Terminal

Attack Controller

Bombardier Steve Connor, uses his spotting scope in an overwatch position during a patrol

with the

Managed Works Team

in Uruzgan Province.

Australian Army 16th Air Land Regiment personnel launch a live Bolide missile from the RBS-70 at a target

over Lake Hart during Exercise Remagen Bridge 19 at Woomera Test Range, South Australia.

The crew of one of the guns of the Hughes Battery, in the front line at ANZAC

A 9.2 inch gun of the 2nd Australian Siege Battery (55th Australian Siege Artillery Battery)

An eighteen pounder of the 30th Battery of Australian Field Artillery

The 14th Battery of Australian Field Artillery in action near Bellewaarde Lake

Darwin, NT. c. 1934. Elevated view of the loading of a 6 inch Mark VII naval gun

2/12th Field Regiment gunners with a captured Italian 75/M37 75mm field gun

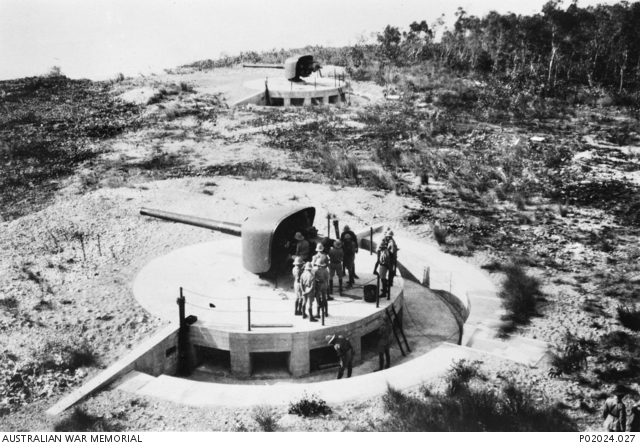

Point Nepean, Victoria Australia 1943-04

Balikpapan, Borneo 1 JULY 1945. Members of 8 Battery, D Troop, 2/4 Field Regiment

Korea. 22 July 1952. Informal portrait of Captain Brien Forward of Lane Cove, NSW

An M2A2 105 mm howitzer of the 104th Field Battery, Royal Australian Artillery (RAA)

Nui Dat, South Vietnam. 1966. Radar equipment for locating and detecting enemy artillery

Unidentified Australian gunners fire their M2A2, 105 mm

howitzer,

towards enemy positions at Fire ...

Baidoa, Somalia. 1993-03-29. A member of 107 Field Battery, 3 Combat Engineer Regiment, with ...

Bombardier Malcom from the 16th Air Defence Regiment attached to HMAS KANIMBLA, mans an RBS70

missile launcher as a coalition Sea King passes overhead.

Bombadier Greg Hunt gives the thumbs up after recovering the Scan Eagle Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV)

at Camp Terendak in Iraq.

Bombardier Glen Swain patrols with (L-R) Gunner Ashley Kerr and Private Joshua Cavanagh in the green zone

of Sinha a village in the Mirabad Valley Region.

High Mobility Rocket Artillery Systems of the United States Army and United States Marine Corps launch rockets during

a firepower demonstration held at Shoalwater Bay Training Area in Queensland, during Talisman Sabre 2021.

109 Battery Alpha detachment, 4th Regiment, Royal Australian Artillery, fire their M777 Howitzer

during a demonstration at Shoalwater Bay Training Area in Queensland, during Talisman Sabre 2021.

Everywhere Whither Right and Glory Lead |

||||