|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Have a Question / Feedback ? | Submit- only questions about this website will be answered | Search Our Site |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of the Crimean War Trophy Gun's | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Crimean War was fought in the Black Sea, Caucasus, Baltic, White Sea and Pacific theatres with the principal fighting occurring in the Crimea where the main focus became the siege of the Russian naval base at Sevastopol. A.J.P. Taylor argues that the war resulted not from aggression but from the interacting fears of the major players: In some sense the Crimean war was predestined and had deep-seated causes. Neither Nicholas I nor Napoleon III nor the British government could retreat in the conflict for prestige once it was launched. Nicholas needed a subservient Turkey for the sake of Russian security; Napoleon needed success for the sake of his domestic position; the British government needed an independent Turkey for the security of the Eastern Mediterranean…Mutual fear, not mutual aggression, caused the Crimean war1. The Crimean War commenced on 23 October 1853 when the Ottoman Empire declared war on Russia. France and Britain declared war on Russia on 28 March 1854. They were later joined by the Kingdom of Sardinia. It concluded on 30 March 1856 with the signing of the Treaty of Paris. During the war 888,000 Russians were mobilized of which 324,478 were deployed. 35,671 were killed in action, 37,454 died of wounds, 377,000 died from non-combat causes and 80,000 wounded. Turkey deployed 165,000 (10,100; 10,800; 24,500; ?), France 309,268 (8,490; 11,750; 75,375; 39,870), Britain 107,864 (2,755; 1,847; 17,580; 18,280) Kingdom of Sardinia 21,000 (28 KIA; 2,138 DOD). The allies landed 56 kilometres north of Sevastopol on 14 September 1854 and six days later commenced to advance towards Sevastopol. They engaged and defeated a Russian force at the Battle of Alma on 20 September. Deciding against a direct attack on Sevastapol the allies prepared for a protracted siege and positioned their troops to the south of the city, the French occupied the bay of Kamiesch on the west coast and the British moved to the southern port of Balaclava. The Russians split their force, the defence of the considerable static defences of the city was primarily manned by the navy whilst the mobile army moved outside the encirclement. The Russians within the siege area began by scuttling their ships to protect the harbour, then used their naval cannon (at least 690 guns from eight ships deliberately scuttled) as additional artillery and the ships' crews as marines. By mid-October the allies had 120 guns in position whilst the Russians had about three times as many. The artillery battle began on 17 October and at the same time 27 ships of the allied fleet pounded the Russian defences and shore batteries. Hoping to disrupt the supply chain between the British base and their siege lines the Russian army attacked Balaclava on 25 October 1854 but were forced onto the defensive. Another attack on the allied forces was undertaken on 5 November at Inkerman. Despite being severely outnumbered the allied troops held their ground. Following this battle the Russians saw that the siege of Sevastopol would not be lifted by a battle in the field, so instead they moved troops into the city to aid the defenders. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The allies had insufficient troops to isolate the city enabling the Russians to bring up regular reserves and reinforcements. According to Capt. Edmund Reilly’s official account of British artillery operations, | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

To arm the [gun] batteries which the enemy constructed where he wished, he had a great Arsenal, a Dockyard and a Fleet, capable not only of supplying his first armament, but also of replacing his guns as soon as disabled. He had at hand an almost unlimited quantity of matériel and supply of labour to repair and strengthen the works which we were called upon to destroy; and the place not being invested, matériel brought from a distance became available for its defence, while the garrison could be continually relieved. To the last hour of the Siege the enemy continued enlarging his batteries, and constructing new ones, nor was he ever deficient in ordnance to arm them. Three thousand pieces which had not been mounted were taken in the place. This unfailing supply of artillery was one of the chief causes of the protracted defence2. During the siege Sevastapol was subjected to bombardment from ship and shore on 9 April, 6 June, 17 June, 17 August and 5 September 1855, normally with associated ground assaults. The last bombardment was the most severe with 307 guns firing 150,000 rounds. On 8 September the allies attacked and despite the unsuccessful British assault on the Great Redan, the French managed to seize the Malakoff Redoubt and the Little Redan, making the Russian defensive position untenable. The Russians retreated to the north, blowing up their magazines and the city fell on 9 September 1855. Both sides were exhausted and no further military operations were conducted in the Crimea before the onset of winter. Tsar Nicholas I died on 2 March 1855 and was succeeded by his son Tsar Alexander II who inherited a war going very badly, economic problems and later a fear of invasion from the West, notably Austria. With the loss of Sevastapol Alexander II feared a defeat of Russian forces and sought peace. The Congress of Paris was convened between the great powers of Europe. Assembled soon after 1 February 1856 when Russia accepted the first set of peace terms after Austria threatened to enter the war on the side of the Allies. The final terms were worked out between 25 February to 30 March 1856. The signing of the Treaty of Paris on 30 March 1856 ended the Crimean War. Following the fall of Sevastopol the allies began recovering Russian guns3 and materiel and shipping them back to their countries. Early in 1856 Sir William Codrington, the British Commander-in-Chief in Crimea, asked Lord Panmure, the Secretary for War, for instructions about the captured Russian guns. Whilst the peace negotiations were going on Panmure saw problems ahead and advised Codrington to prepare for offensive operations.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

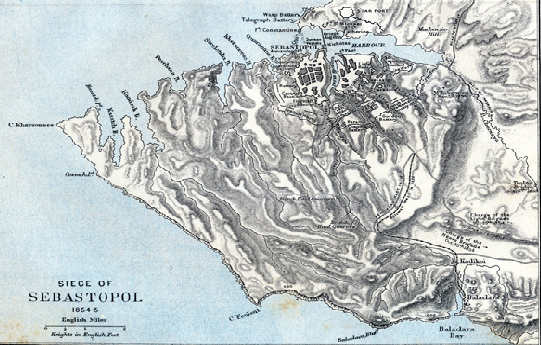

| Map by cartographer FS Weller published in the ‘School Atlas of English History’ in 1895 showing the territory between Balaclava and Sevastopol. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

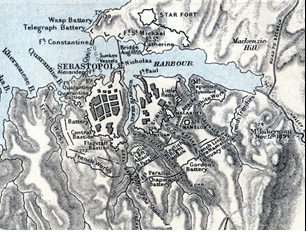

| Enlargement of the area around Sevastopol from the map above. The various forts can be seen including The Redan and Malakoff. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Panorama ‘Siege of Sevastopol’ painted by Russian artist Franz Roubaud depicts the attack on the Malakoff Battery on 6 June 1855 in which 173,000 French and British troops were repulsed by 75,000 Russians. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Enlargements from the panorama above showing the strength of the Russian defences. A variety of Russian guns can be seen. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The attack on the Malakoff by William Simpson. Malakoff was the main Russian fortification before Sevastapol. The print published in October 1855, less than two months after the battle show French soldiers on the left and Zouaves from the left foreground attacking the Russian position. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Despite the French shipping their share of the guns back to France Panmure was not enthusiastic about recovering the guns. The Army however, got on with recovering as many Russian guns as possible. Once peace was declared the British were keen to get their troops and spoils of war home as quickly as possible. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 94 bronze and 1,079 iron guns were shipped back to Britain but a decision on what would become of them was not made. Panmure was against the parading of the guns ‘and so keep open the sores of war after the healing hand of peace has been applied4. It was not until January 1857 that the authorities settled on a solution that included the distribution of guns to towns and cities deserving of them. Nearly 300 guns were distributed in this way including to the Dominions. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| January 1857 that the authorities settled on a solution that included the distribution of guns to towns and cities deserving of them. Nearly 300 guns were distributed in this way including to the Dominions. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In a letter to the Under Secretary for War, dated 20 September 1857, Mr W.F. de Salis5 wrote: | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| London Chartered Bank of Australia, 17 Cannon-street. City, 20th September, 1857. Sir,-The attention of several gentlemen connected with the Australian colonies having been attracted by the liberality evinced by Lord Panmure, in bestowing upon certain towns in this country trophies obtained during the late war with Russia, I have the honor to inform you that they are desirous, if possible, to secure for the Colonies which they respectively represent similar mementos of that short but eventful struggle. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I am therefore instructed, on behalf of those gentlemen, to request that you will have the goodness to submit to Lord Panmure their respectful solicitation that his Lordship may be pleased to cause to be reserved for the Australian Colonies a few of the captured Russian guns, until such time as they shall be officially applied for by the proper local authorities, and arrangements made for their conveyance and reception | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In undertaking to be the medium of this communication, I beg to add that I feel assured that independently of other considerations, Lord Panmure will be glad of the opportunity thus presented of marking his appreciation of the loyalty and generous sympathy exhibited by the inhabitants of the Australian Colonies generally, in their ready and munificent contribution to the " Patriotic Fund6," proving that, however distant, their best feelings are identified with the honor of the British nation, and the valor of its brave defenders. I have the honor to be, Sir, Your most obedient servant, WM. FANE DE SALES.7 (sic) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The War Office reply of 5 October 1857 stated ‘Lord Panmure desires me to acquaint you in reply that he has already informed the Secretary of State for the Colonies, that he is prepared to present, on behalf of her majesty, to each of the colonies of New South Wales and Victoria, two guns captured from the Russians in the late war. I am to Add, that a certain number in addition have been set apart, and should the inhabitants of other colonies be desirious of having these trophies presented to them, application should be made through the Governor to the Secretary of State for the Colonies8’. The letter was signed J.W.Storks. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The contributions to the Patriotic Fund by the various colonies9 were: | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1A.J.P. Taylor, The Struggle for Mastery in Europe: 1848-1918 (1954) pp. 60-61 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2Britain’s Crimean War trophy Guns: The Case of Ludlow and the Marches. Roger Bartlett, Roy Payne. History, The Journal of the Historical Association. P653 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3https://downrabbitholes.com.au/drake/william-henry-drake/crimea/raglan/ describes the distribution of the stores at Sebastopol as published in the Royal Cornwall Gazette of 7 December 1855. This indicates there were 128 brass guns and 3,711 iron guns. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 Britain’s Crimean War trophy Guns: The Case of Ludlow and the Marches. Roger Bartlett, Roy Payne. History, The Journal of the Historical Association. P659 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5 William Fane de Salis (1812-1896), third son of Jerome, 4th Count de Salis-Soglio, visited Australia 1842, 1844, 1848 to pursue business opportunities in Australia.. Upon return to Britain among his appointments held were Directorship of the Union Bank of Australia, Director of the Australian Agricultural Co and Deputy-chairman then Chairman of the London Chartered Bank of Australia. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6The Royal Patriotic Fund was created in 1854. Queen Victoria, concerned for the well-being of the widows and orphans of British servicemen dying in the Crimean War, made an appeal for public donations. (The State did not at that time assume any responsibility for the dependants of its soldiers and sailors lost in conflict.). | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7The Argus 12 January 1858. p5 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Next | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Everywhere Whither Right and Glory Lead |

||||