|

BRITISH ARTILLERY IN WORLD WAR 2 |

|

ANTI-TANK ARTILLERY |

A description of the anti-tank artillery tactics and gunnery used by the Royal Artillery and the artilleries of British Commonwealth armies.

|

Updated 14 June 2014 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ANTI-TANK PUBLICATIONS |

The need for anti-tank arose with the emergence of tanks. Since tanks were 'point targets', and moving ones at that, the obvious way of engaging them was with direct fire. This meant having the guns deployed where they could see and engage tanks. Anti-tank tactics were direct fire tactics. Of course from an artillery perspective this meant abandoning firepower mobility although during World War 2 (WW2) both concentrated and destructive indirect artillery fire was used effectively against tanks. In mid-1940 the British view was 'tanks well served and boldly directed have established a superiority on the battlefield which is out of all proportion to their true value' and 'It has been proved that tanks, for all their hard skin, mobility and armament achieve their more spectacular results from their moral effect on half-hearted or ill-led troops'. The latter was encouraging to the cavalry traditionalists, the great believers in 'shock action'. This account is about anti-tank artillery.

Although the first 'tank versus tank' engagement occurred during the German's Lys offensive against the British in the spring of 1918, it is often forgotten that in WW2 tanks were not the primary anti-tank weapon. This was the role of anti-tank guns, whether self-propelled (SP) or towed.

During World War 1 anti-tank was regarded as just another role for normal field artillery. In the 1920s the British infantry division organisation included a 'light brigade' (regiment) equipped with 3.7-inch Howitzers, its task being 'accompanying artillery' for the infantry (although the British did not use this continental term) and one of its roles was anti-tank. This organisation was abandoned in 1935/6 and the light brigades were converted to army field brigades. However, the traditional role of RHA was supporting mobile formations and when the first 'mobile division' was formed in 1937 it was supported by two RHA regiments with 3.7-inch Howitzers. This was most unsatisfactory, not least because the 3.7-inch was useless for anti-tank (until new ammunition in 1944), it was swiftly changed in 1938.

Anti-tank remained a secondary role for field and AA batteries, with the option of being a primary role in exceptional circumstances when individual guns could be positioned in forward defences. Anti-tank as a secondary role meant that the guns remained deployed in their field (or AA) artillery gun positions. As a primary role it meant they deployed as individual guns or sections as part of an anti-tank plan. The primary anti-tank weapons until 1938 were anti-tank mines and rifles. The doctrine was that in the forward defensive areas anti-tank defence was the responsibility of the infantry brigade commanders with artillery commanders organising a second line of defence based on the field artillery deployment. Behind this the general staff arranged centres of resistance and protection for roads, bridges and defiles.

In 1938 British infantry division anti-tank regiments RA with 4 batteries were formed by converting 5 regular and 5 TA field regiments, and 5 TA infantry battalions to the new role by 1939, and then doubling the TA regiments that year. This gave 100 anti-tank batteries formed or forming at the outbreak of war. They were equipped with the new 2-pdr anti-tank gun designed in 1935. However, others, such as Canada and Australia didn't form anti-tank units until after the outbreak of war. British anti-tank regiments are listed here.

Infantry brigade anti-tank companies for regular army brigades, comprising infantrymen, were also formed in 1938. Companies for TA divisions didn't start forming until after the outbreak of war and in many cases they did not form until after mid-1940 and a few did not form until early 1941, although by January 1941 all those in regular infantry divisions had disbanded! Some of these companies continued until early 1942. They were equipped with 9 anti-tank guns, mostly Hotchkiss 25-mm because the artillery anti-tank regiments had priority for 2-pdr. Anti-tank platoons in infantry battalions started forming in late 1940 or early 1941 as equipment became available. This account does not cover specifically infantry anti-tank matters.

The result was that at the outbreak of war anti-tank practices were under-developed because it was not a well established specialist discipline and specialist units had existed for barely a year. Unit organisation and doctrine for anti-tank deployment, tactics and gunnery all evolved rapidly during the following three years.

Nevertheless, key elements of doctrine had been established. First, anti-tank guns used defilade or reverse slope positions whenever possible to provide defence in depth on the most likely tank approaches. They accepted a field of fire limited to 500 yards if necessary. Second, anti-tank tactics emphasised not opening fire too soon. While the obvious reasons were accuracy and penetration at longer ranges, the critical factor was that guns were stationary and could be out-manoeuvred by the attacking tanks. Although not well recognised before the outbreak of war another issue was that an anti-tank gun that revealed itself too soon was vulnerable to neutralisation by both indirect and direct fire including machine guns. In 1926 the tactical doctrine was that the most effective range for anti-tank shooting by an 18-pdr was between 1000 and 400 yards at 8 - 12 rpg/minute and this generally remained the practice.

It was also recognised that isolated anti-tank guns were vulnerable to infantry attack so they needed to be in a defended locality. This affected infantry defence planning, which was not generally to site defensive positions for the optimum use of anti-tank guns. In practice the infantry tended to the view that anti-tank guns were there to protect them from tanks. This meant there was tactical tension between the role of anti-tank guns to defeat armoured mobility and that of infantry to hold ground, these were not always the same thing. The problem was that the attacker has the initiative and a mobile attacker could concentrate their forces whereas the defender endeavoured to 'cover' everything and therefore tended to spread out their forces. But effective anti-tank action required concentrated firepower in depth not 'thin red lines'.

Whereas field artillery organisations were stable from 1940 onwards, the situation for anti-tank regiments was similar to armoured divisions; organisations evolved throughout the war. Of course part of the issue was that anti-tank gun technology evolved to meet the threat of increasing armour protection and the need for both offensive and defensive tactics. Added to this was the introduction of more powerful but heavier towed and self-propelled (SP) anti-tank guns.

The unit structure followed the artillery pattern, albeit with more guns than field artillery. Regiments comprised 3 or 4 batteries, each with 3 or 4 troops, which in turn had 2 sections each with 2 guns. Total strengths varied with the number and type of guns. RHQ comprised 5 officers and, after 1940, 6 to 8 in a battery depending on the number of troops. Figure 1 gives the outline organisation as it was from early 1944 for a regiment in an infantry division without any SP guns. It excludes the RA repair tradesmen. Some War Establishments for the later years of WW2 are here.

Figure 1 - Outline Organisation

Both overall and detailed organisation evolved through the war, the only unchanging feature was the troop of 4 guns organised in 2 sections. In contrast to the stable rank structures throughout the field artillery, those in anti-tank evolved:

At the end of 1942 anti-tank regiments changed to a new form of war establishment (WE). Instead of the establishment being for the complete regiment, there was a WE for the HQ of an anti-tank regiment designed to command 3 or more batteries, and separate WEs for each type of battery. Troop strengths also varied, not just with the type of gun (they needed different sizes of gun detachment) but more generally. For example at the end of 1942 a 6-pdr troop comprised 1 officer and 30 soldiers, by mid 1943 it was 1 and 31 and by early 1944 1 and 33, and this was in a climate of decreasing manpower where WEs were being 'shaved'. Battery strengths went from 6 and 110 with 12 × 2-pdrs in 1942 to 7 and 158 for a battery with 8 × 17-pdr and 4 × 6-pdr in early 1944 or 7 and 169 for a battery with 12 × M10.

The main overall organisational points were:

However, after Dunkirk there was a severe shortage of anti-tank guns and neither anti-tank regiments nor anti-tank companies had been established in British or Indian formations outside UK and France. Anti-tank equipment priority was given to formations in UK and the mainly Dominion divisions arriving in the Middle East from 1940.

In mid-1942 it was decided to increase divisional anti-tank regiments to 64 guns in 4 batteries in N Africa, the rationale being the shortage of natural tank obstacles in the desert. However, this only lasted a few months, mainly due to manpower constraints. In late 1942 when most 2-pdr anti-tank guns had been replaced by 6-pdr in N Africa regiments of 3 batteries became the standard, with the principle that one battery should be SP. However, a few months later the organisation for the Middle East was approved as 4 batteries each with 12 guns in 3 troops.

By September 1943 the official position for European Theatres was:

At the beginning of 1944 the official WEs permitted divisional anti-tank regiments to comprise 4 batteries each with 8 × 6-pdr and 4 × 17-pdr, or 2 batteries with 12 × 6-pdr and 2 with 12 × M10, or 4 batteries each with 8 × 6-pdr and 4 × M10.

However, there was considerable dissatisfaction with these organisations, what was wanted, and was duly agreed and approved was:

The following month a specialised anti-tank battery organisation was approved for 'assault' units (meaning amphibious assaults). These batteries had 2 troops of 6-pdr and 1 of M10. The reason for this was the policy that only tracked vehicles would cross the beaches for the first 8 hours of a landing. However, in August 1944 experience in Normandy led to a revised organisation for batteries in infantry divisions, a merging of the 'normal' and 'assault' organisations. Batteries became 1 troop 6-pdr, 1 troop towed 17-pdr, 1 troop SP 17-pdr to provide an effective mix of capability reflecting strengths and weaknesses of the various guns.

Starting in 1943 infantry type divisions in India had a composite LAA/ATk regiment instead of one regiment of each as in western theatres, although most divisions in India had never had an LAA regiment and a LAA/ATk regiment had been formed a year earlier, possibly for the Indian armoured division. These regiments were generally formed by a pair of LAA and anti-tank regiments exchanging two batteries. They lasted until September 1944 when all the LAA/ATk regiments in 14 Army became anti-tank regiments with 3 batteries, dual equipped with a 6-pdr anti-tank gun and 3-inch mortar for each of their 36 detachments.

Anti-tank was the one area of artillery organisation where there was national diversity. By the end of the war Canada had two types of anti-tank regiment, corps and armoured division regiments had 48 guns 50:50 towed and SP 17-pdr, but infantry division regiments had only 36 guns, still 50:50. Australia retained the 48 gun regiments, all 6-pdr, for the home defence divisions, but the jungle divisions were reduced to a single battery from a corps anti-tank regiment. All Australian anti-tank regiments were renamed 'Tank Attack Regiments' in 1943. In the final year of the war the AIF divisions' retained their tank attack regiments but anti-tank was little used and Australian batteries employed 4.2-inch mortars, 75-mm howitzers and acted as infantry.

Most British anti-tank ammunition during WW2 was solid shot, which relied on kinetic energy to penetrate armour. KE is the product of the mass and velocity of the shot.

However, soon after WW1 an armour piercing HE shell had been developed for the 18-pdr field gun (such shells had been common for naval guns), and the original design of 25-pdr ammunition had been for an armour piercing cap for 25-pdr HE, this design was unsuccessful. 2-pr also had a AP shell with a very small bursting charge and a base fuze.

Later in the WW2 a shaped charge (HEAT) shell was developed and issued to 3.7-inch Howitzers in Burma, although in the event it was never needed. HEAT was also used with the PIAT. To these can be added work on recoilless guns, including the 4.7-inch anti-tank using HESH that led to the post-war 120-mm BAT family, during the war the size of its ammunition and its logistic implications found little favour.

Wartime developments in anti-tank (and tank) gun ammunition addressed two matters, improving penetration of shot and flashless propellant.

At the outbreak of war the standard anti-tank ammunition was a solid armour piercing (AP) shot fitted with a tracer. Throughout the war anti-tank guns used fixed ammunition (ie the cartridge and shot were a single fixed item, unlike other artillery ammunition). Improvement to the penetrative capability of AP shot went through 5 stages:

APDS provided better penetration than APCBC but the latter did greater damage when it penetrated so both were used with APDS being used when penetration by APCBC was less than certain. In addition there were practice projectiles (PP) for all calibres. These were generally reduced in lethality and range. AP shot was available for 40-mm Bofors LAA guns throughout the war. However, HE was useful, during the first German attack on Tobruk the first rounds fired at tanks by 25-pdr were HE. The first caused a Pz KfW Mk IV to catch fire, with the second another tank lost its turret.

The following table summarise the main characteristics of anti-tank ammunition, most were fitted with tracers and there were also practice rounds for each calibre. The penetration figures are for standard tests and should be viewed in terms of their relativity and not actual penetration of tank armour.

Table 1 - Summary of Anti-Tank Shot Characteristics

|

Ammunition |

Calibre |

Weight |

MV |

500 yds, 30° |

1000 yds, 30° |

|

2-pdr AP |

1.58 inch |

2 lb |

2616 f/s |

53 mm |

42 mm |

|

6-pdr Mk II AP |

2.24 inch |

6.25 lb |

2800 f/s |

75 mm |

63 mm |

|

6-pdr Mk II APC |

2.24 inch |

6.25 lb |

2775 f/s |

|

88 mm |

|

6-pdr Mk II APCBC |

2.24 inch |

7 lb |

2600 f/s |

|

95 mm |

|

6-pdr Mk IV AP |

2.24 inch |

6.25 lb |

2925 f/s |

|

74 mm |

|

6-pdr Mk IV APC |

2.24 inch |

6.25 lb |

2900 f/s |

|

|

|

6-pdr Mk IV APCBC |

2.24 inch |

7 lb |

2725 f/s |

|

|

|

6-pdr Mk IV APCR |

2.24 inch |

3.97 lb |

3528 f/s |

|

100 mm |

|

6-pdr Mk IV APDS |

2.24 inch |

3.25 lb |

4050 f/s |

|

143 mm |

|

17-pdr AP |

3 inch |

16.94 lb |

2900 f/s |

123 mm |

113 mm |

|

17-pdr APC |

3 inch |

17 lb |

2900 f/s |

|

118 mm |

|

17-pdr APCBC |

3 inch |

17 lb |

2900 f/s |

|

|

|

17-pdr APDS |

3 inch |

7.63 lb |

3950 f/s |

|

231 mm |

|

25-pdr Mk 2 AP |

3.45 inch |

20 lbs |

1850 f/s |

62 mm |

54 mm |

Conversion factors:

inches to mm - inches × 25.4

mm to inches

- mm ÷ 25.4

feet to metres - feet × 0.305

pounds to kilos - pounds

× 0.454

From mid 1943 the ammunition loads carried within each troop were:

Before 1943 loads were higher and in 1944 HE ammunition was introduced, see the 'Other Firepower' page. Development of 6-pdr anti-personnel cannister was stopped in 1944.

Complete round weights varied with the shell. However, weights for AP were 6-pdr, 13 lbs and 17-pdr, 35 lbs. The standard distribution of ammunition between vehicles is shown in the war establishments here.

The importance of concealment for anti-tank guns meant that their flash and smoke was significant because it made them easier to spot when they fired, particularly at night. Flashless propellant, using added mineral salts became available in WW2 as did 'triple-base' propellants. The problem was that while salt additives reduced the amount of flash they also increased the amount of smoke, which hindered the layer and betrayed them in daylight. The result was that policy kept changing, and at the end of 1941 anti-tank was removed from the list of flashless propellant priorities, only to be added again later in 1942. By this time cooler burning triple-base propellants were used, which reduced barrel wear, and caused less muzzle blast which reduced dust - another 'giveaway'.

2-pdr Mk II, selected in 1936 from prototypes designed by Vickers Armstrong (Mk I) and by the Design Department at Woolwich (Mk II ). The Mk II was selected although Vickers produced it, trials showed its armour penetration was some 50% better than its equivalent German 37-mm. The same 2-pdr ordnance and ammunition (2 lb 6 oz shot) was used to arm tanks. The Littlejohn conversion that slightly increased 2-pdr performance did not arrive until 2-pdr have been replaced in anti-tank regiments. The 2-pdr had a 5 man detachment and weighed 1760 lbs in action.

25-mm Hotchkiss introduced in 1939 as a stop-gap to equip infantry anti-tank companies and some TA anti-tank regiments. It weighed 685 lbs in action.

37-mm Bofors, originally ordered for Sudan, it equipped 3 RHA and some other batteries in the Western Desert 1939-41.

6-pdr 7-cwt Mk II, production deliveries started at the end of 1941 and reached N Africa in about April 1942. It had superior anti-tank performance to the 25-pdr and its arrival enabled 25-pdr to revert to its primary role. 6-pdr was a well established British calibre (2.244 inches - 57-mm) and a pilot anti-tank gun had been ordered in 1938. The ordnance design was completed in early 1940, but the carriage design was not finally approved until early 1941. At the end of 1940 the decision was made not to change an existing 2-pdr production line to 6-pdr but to wait until a new production facility was established. In part this was because 2-pdr could be produced quickly (at about 6 times the rate of 6-pdr) and the need was for production volume, although it was expected that German tanks would be up-armoured after their trials of captured 2-pdr. A single baffle muzzle brake was approved at the end of 1942 and a month or so later all production had changed to the longer barrelled 6-pdr Mk IV and deliveries had started. The 6-pdr used in airlanding batteries had a modified axle so that it could be carried in a Horsa glider. The US built the Mk IV without its muzzlebrake as the 57-mm M1. The 6-pdr gun had a 6 man detachment, weighed 2520 lbs in action and a top-traverse of 45 degrees left and right.

3-inch 16-cwt, in 1941 100 outdated 3-inch 20-cwt AA guns were converted to anti-tank guns. These AA guns already had 12½ lb AP shot and telescopes. 50 ordnance were mounted on Churchill tanks and 50 on new 17-pdr carriages, the latter were issued equally to Home and Middle East Forces, the former had very limited traverse (7 degrees) and were only issued to Home Forces.

3-inch M10, the need for a SP anti-tank gun led to the US M10 being introduced in mid 1943, initially for armoured divisions. This equipment comprised the US 3-inch AA Gun M7 mounted on a M4 medium tank carriage with an open top turret giving all-round traverse. The M10's turret was not well balanced and this caused problems in some circumstances. The UK intention had been to replace M10 with a new US SP anti-tank gun 3-inch T70, in the event this gun was not adopted because it was incompatible with 17-pdr.

17-pdr Mk 1, design of this 3-inch gun started in early 1941 and deliveries started, covertly, to N Africa at the beginning of 1943. The first 100 guns were mounted on 25-pdr carriages and called carriage 17-pdr Mk 2. The 17-pdr had a 7 man detachment, weighed 4625 lbs in action and a top-traverse of 30 degrees left and right.

32-pdr, the requirement for a yet more powerful anti-tank gun started in 1942. The 32-pdr was the eventual result, 2 prototypes were produced, trials were completed after WW2 and the project was then stopped.

In addition captured anti-tank guns were also used, mostly in N Africa including portee. However, only the Italian 42/37-mm of the anti-tank battery in the Raiding Support Regiment in 1944-5 appear to have been part of an official establishment, although the Australian 2/4 ATk Regt had few Bredas in Singapore in January 1942. This regiment had been first equipped mostly with a 75-mm. It is not clear what this gun was, or where they came from. It might have been a US built 75-mm on 18-pdr Mk 1 carriage field gun provided under Lend Lease, or something else.

Finally, the 0.55-inch Boyes anti-tank rifle was issued to 'all-arms' for anti-tank defence until it was replaced by the PIAT (Projector, Infantry, Anti-Tank) in 1943.

British anti-tank doctrine emphasised the need for tactical mobility equal to infantry. This meant fast reconnaissance and battle procedure, rapid cross country movement and rapid obstacle crossing. However, anti-tank guns also needed good concealment and therefore sometimes had to be man-handled into position. Wheels to support the trail while manhandling were developed for both 6-pdr and 17-pdr. Wide shields were an additional complication because they made it difficult to directly push the wheels from either direction, although both 6-pdr and 17-pdr wheels had eyes for drag ropes. The 17-pdr's weight made any manhandling hard work.

Portee anti-guns became popular in N Africa. The practice probably originated with the 25-mm in the BEF because this was not a robust gun and carrying it was less damaging than towing. The specification for portee 2-pdr appeared at the beginning of 1940, but didn't permit firing from on-board. In August 1940 development started for a SP 2-pdr based on a Lloyd carrier but it never entered full scale production. Middle East Command consequently developed a local portee for 37-mm on Ford 30-cwt trucks. Initially portee anti-tank guns were effective against German and Italian tanks in N Africa, and proved useful in Greece. However, once the Germans got over their surprise they became less useful as 1941 progressed, they were no match for a tank even if they could move quite fast, they were unarmoured and had to operate within range of tanks' machine guns as well as their main armament. Firing from portee became increasingly constrained by doctrine about its appropriate use.

Portee 6-pdr, based on a 3 ton truck was introduced, although it could be fired when portee it was not a great success, and at the beginning of 1943 the policy decision was taken to abandon portee except in motorised infantry battalions. However, an SP 6-pdr was introduced, called Deacon, it equipped a battery in each regiment. It was based on the Medium Artillery Tractor (Matador) chassis, and had an armoured minimal body and cab with a fully rotating armoured turret mounted on what would have been the centre of the cargo platform.

The 17-pdr, being bigger still presented another challenge. Portee was never considered and three SP forms emerged:

However, anti-tank gun tractors were the real problem and a good one did not appear during the war. The problem was the need for a vehicle that had the necessary tactical mobility for the forward areas while towing the gun and carrying its detachment and ammunition. Anti-tank was only one part of the gun tower problem, which also applied to 25-pdr and 40-mm AA. In 1943 the decision was made to develop a tracked 'Universal Gun Tractor', which finally appeared as the CT 26 (later renamed Oxford Carrier) after the war. In the meantime interim solutions were required.

Before the adoption of portee, 2-pdr was towed by an 8-cwt truck, one of the problems with 2-pdr towing was its small diameter wheels, which required a lowered towing hook on the vehicle. Various vehicles were tried for towing 6-pdr. Eventually, the Lloyd carrier became the norm and a re-configured Lloyd carrier with the engine forward instead of at the rear gave more space. Before this towers included the Field Artillery Tractor with modified towing where 3-ton portee was unsuitable for the unit's role, the 30-cwt 4 × 4 used for 2-pdr portee and a 30-cwt modified with a lower body. An armoured 15-cwt that was unable to carry the full detachment and first line ammunition was also used in the mid-war period.

17-pdr provided further challenges, not least because it was heavier than a 25-pdr and its ammunition was a lot larger than 6-pdr. Initially 3-ton portee were used for towing, but the Field Artillery Tractor was used, as was a modified 3-ton with lowered body and a 30-cwt 4 × 4. Lloyd carriers were also employed and when M5 halftracks became available in the summer of 1944 these were used as both tractors and section ammunition vehicles. However, the innovation was to use tanks. Most of the work centred on the Crusader Mk 3, although stocks were limited. It involved removing the turret, providing seating and ammunition space and adding tow hooks back and front (for pushing the gun into a concealed position). They eventually entered service with some corps anti-tank regiment as the Crusader Mk 3 Gun Tower Mk 1 in mid 1944. However, it appears that some Shermans may have been locally modified in Italy. M10 were also modified to enable them to tow 17-pdr.

A most important component of an anti-tank gun is its sight, a 'sighting telescope' in British terminology. With the exception of the 25-pdr which also had a telescope, field and medium guns would engage tanks using their normal dial sight. In poor light or when the target couldn't be seen through an optical sight then an open sight (basically the same sort of thing as a rifle sight) was used. Range was set using a range drum that was part of the sight mount. This range drum 'clicked' when changed so that the layer could change the range by feel without removing his eye from the telescope. The graduations on this range drum determined the maximum possible anti-tank range, longer range indirect fire was possible but required a field clinometer to lay in elevation according to the data in the Range Tables.

The normal pattern for anti-tank telescopes was 'cross-hairs' their full height and width and vertical graticules aligned in a horizontal row that measured an angle (usually graduated at 30 second intervals). These marks were on a movable diaphragm in the sight that could be adjusted as part of the sight testing and zeroing procedures. Early model telescopes such as the No 24 used with 2-pr and No 22C used with 6-pdr and 25-pdr had a ×1 magnification and 21 degree field of view. The No 41 used with 17-pdr initially had the same magnification and field of view. However, 17-pdr's longer range led to demand for greater magnification and in late 1943 the No 51 with ×3 magnification became available for 17-pdr. The issue was that magnification reduced the field of view, making it more difficult for the layer to acquire the target, particularly at shorter ranges. Later model telescopes also had graticules that could be illuminated for night shooting. An added complication was that British drills required the layer to keep layed on the target when firing, this meant a sight that wouldn't cause damage if the gun moved suddenly back when firing - black eyes were common among layers newly converted from 2-pdr to 6-pdr.

Guns were fitted with an open sight for use in conditions where visibility was poor. These comprised an open foresight blade and rear 'aperture that were part of the sighting telescope mount with the range drum. The rear aperture could be set with lead using lead drum with 'clicks' in the same manner as the range drum.

Indirect fire sights were later introduced, see the 'Other Firepower' page.

A useful ancillary was the 2-inch mortar. One was issued to each anti-tank section starting in 1943, and provided with smoke and illuminating ammunition. The former enabled the gun to screen itself if it had to move, the latter gave a capability to engage targets at night. The ammunition load for each mortar was 10 rounds each of smoke and illuminating, and a further 4 rounds of each in unit transport and 2nd line.

Anti-tank units did not hold anti-tank mines but they were trained to fuze and lay them. A mine detector was issued to each troop in mid-1943. In mid-1944 trip flares were issued. However, it wasn't until mid-1942 that every man was issued with a small arm. Until that time each gun detachment had a LMG and 2 rifles. Use of enemy anti-tank guns was part of anti-tank training.

In late 1943 double shields were authorised for anti-tank guns and for new production 25-pdr, which also gained hinged bottom flaps. Standalone side-shields were also designed for anti-tank guns, these too were double thickness - two shields separated by spacers. In the event the side shield for 17-pdr proved too heavy for field use and only one was issued to each 6-pdr.

One of the problems with the open top SPs was their vulnerability to HE bursting in the trees above them as well as normal airburst shells. The edges of woods were good places for SPs because they provided concealment. In consequence steel plates were fitted to some SPs about a foot above the top of the fighting compartment. Because surprise was a key element in anti-tank tactics camouflage and concealment was vital, and guns had to conceal themselves against both air and ground observation. In keeping with normal British practice all guns and wheeled vehicles had a scale of garnished nets, and guns and armoured vehicles had 'shrimp nets'. Garnish could be changed to ensure that the nets best matched the background and hessian sheets coloured either earth or dull green was also available as was coloured steel wool mounted on wire netting. Of course local materials were also widely used for concealment.

Anti-tank units were not well endowed with wireless. Regiments had a rear link detachment provided by H Section of the Divisional Signals Regiment's No 2 Company, this linked regimental HQ to divisional HQ. Wireless was also provided to link regimental HQ to each battery HQ. In mid-1943 No 18 sets were authorised for battery and troop HQs, but without any additional men or vehicles. However, the battery was not in wireless contact with brigade HQ, neither did troops have wireless to communicate with local infantry battalions.

There were changes in mid-1944, by this time SP guns were issued and were fitted with No 19 sets, so their battery and troop HQs also adopted these sets. No 18 sets were issued to towed guns in the corps anti-tank regiments, which also used No 19 sets in all their battery and troop HQs. The need for wireless sets with towed guns in divisional regiments was recognised, but the resultant need to increase the number repair technicians in the divisional signal regiments made it impossible due to manpower shortages.

Line remained the means of communication from troop HQs to guns. However, in early 1943 a pair of sound powered telephones with head and chest sets had been authorised for each gun to enable fire control when the detachment commander was positioned some distance to the flank of his gun.

Anti-tank gunnery was primarily concerned with laying and the drills the detachment should use. Anti-tank gun detachments numbered from 5 to 7 men depending on the equipment. The 3 most important members were:

The other detachment numbers ensured that No 2 had ammunition and were ready to move the trails if required. However, Number 6 might also act as 'link number' immediately behind the gun to relay orders from the No 1 when he was observing from his gun's flank, to confirm that the layer had acquired the correct target and that the opening range was correctly set on the range drum - duties of the No 1 when he was at his gun. The key was that the No 3 did exactly what the No 1 ordered.

Target selection evolved during the war, but it was always stressed that tanks operated in groups, not individually, so anti-tank engagements were not assumed to be one-to-one. This also reflected the tactical reality that tanks could concentrate far more easily than anti-tank guns could. Initially the general principle was to engage the nearest tank when it reached a range at which the No 1 was confident it would be hit. However, tactics evolved so the principle became to engage tanks in the order of the threat they presented. For example a well positioned hull down tank was more of a threat than a closer one moving in the open. 2-pdrs were supposed to open fire at a range of not more than 500 yards, and have a maximum range of 600 yards. The corresponding ranges for 6-pdr were 800 and 1600 yards.

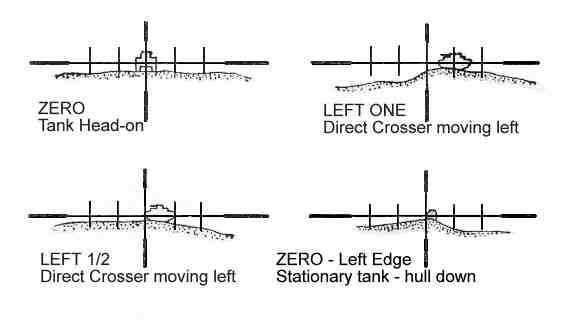

Until the beginning of 1942 British anti-tank gunnery used a 'false range', they aimed low and added a few hundred yards depending on the actual range. From the beginning of 1942 they adopted zeroing of anti-tank guns, usually using a tank sized target at 500 yard with the aim point being centre of mass. This meant the actual range could be set on the range drum, part of the drill for coming into action was to prepare a range card for recognisable objects in the zone of fire. They also issued simple tables for lead depending on range and speed and whether the target was a 'direct crosser' (45 - 90 degree approach angle) or 'diagonal crosser' (15 - 45 degrees). This was related the lead graticules ('lead units') in the anti-tank telescopes. Of course the time of flight of the shot from high velocity anti-tank guns at normal battle ranges was under 1 second, and a tank moving at about 15 mph covered about 7 yards in this time. A 'direct crosser' at 15 mph required a lead of 1 and a 'diagonal crosser' a half, the smallest lead order was a quarter.

Figure 2 - Anti-tank Sight Aiming - Graticule Method

The angles subtended by the graticules both vertically and horizontally were all part of the layer's knowledge

In early 1943 'central laying' was approved as an alternative to graticule laying. This meant that the layer set the lead on the lead drum and aligned his centre graticules with the target. In either case the layer tracked slightly ahead of any crossing target and then let the target move onto his graticule aimpoint when the gun was loaded and he as ready to fire.

Anti-tank engagements were conducted by the No 1 giving initial orders to identify the target relative to the centre of arc, describing it, ordering the range and lead, and ordering fire. He then ordered corrections using 'Add' or 'Drop' for range (these were cumulative) and a new lead (not cumulative). These corrections were judged by observing the tracer to see where the shot went relative to its target. By 1943 ranges and corrections were always ordered to the nearest 200 yards unless the target was hull down in which case 100 yards was used.

The following table, based on firing table probable errors, shows the inherent direct fire accuracy of anti-tank guns when their MPI was on the target centre (ie no human errors). In operations worn guns and other mis-alignments could reduce the chance by up to half at shorter ranges and to a quarter at longer ranges. In the first years of the war training material was issued detailing the most vulnerable areas of enemy tanks. This may have had some use for very short range engagements with infantry anti-tank weapons. It was unrealistic at longer ranges and the 1942 doctrine of 'centre of mass' ended it as far as anti-tank artillery was concerned. Trials also established that a 2 or 6-pdr at the end of its barrel wear life would hit only 18 inches low at 1000 yards.

Table 2 - Chance of Hitting a Vertical 6 ft × 6 ft Target

|

Gun |

1000 yds |

2000 yds |

5000 yds |

|

2-pdr |

90% |

40% |

1% |

|

6-pdr |

96% |

55% |

3% |

|

17-pdr |

98% |

80% |

15% |

|

25-pdr (Chg super) |

80% |

45% |

7% |

Of course teaching laying drills were not the end of the matter. Problems included mud from the shield being thrown onto sights when firing in wet conditions and similar results from ground mud when muzzlebrakes were fitted and threw up mud. The solution to this obscuration was to use open sights. For night shooting 2-inch mortar flares were used to silhouette the target.

However, the tactics of an anti-tank engagement were also critically important. These were the responsibility of the Number 1. These circumstances of an NCO always engaging the enemy according to his own judgement, without immediate direction or orders from his troop or platoon commander, appears to have been unique to anti-tank.

The troop commander' role was mostly reconnaissance and administration, he did not control the fire of his troop when engaging tanks. However, he usually established an observation post and could order guns to move to their second positions so that they could concentrate fire on an enemy tank thrust. By 1943 experience had taught that there was usually an hour or two's warning of a tank attack and its direction, this gave time to adjust anti-tank positions to meet the threat. In defence the gun tractors were held in troop wagon lines, although were ready to move guns to other positions.

In 1939 MTP 19 stated that the 'essence of anti-tank artillery tactics is surprise action from well concealed positions at effective range'. This placed a premium on well trained detachments that operated independently once battle started. Anti-tank guns selected their own targets and engaged them independently. This all meant that training the Numbers 1 of anti-tank guns was of paramount importance. Of course training the Numbers 3 (layers) was also vital, although British doctrine was that 'the Number 1 hits the tank aided by the layer'.

A 1942 artillery training instruction described the Number 1 as being 'what the eyes and brain are to the rifleman' while Number 3 was 'as the muscles and co-ordination of eye and hand are to the rifleman'. It also emphasised 'selection of the correct type of NCO for training as a No 1 is the first essential. Requirements are, a stout heart, a quick eye, and plenty of common sense'.

Anti-tank gunnery was not easy, in the first years of the war first-round hits occurred in less than 50% of occasions in training, but in the second half it rose to over 70% as training methods improved. The main problems were bad judgment of distance and speed, incorrect fire orders by Numbers 1, bad loading and Numbers 3 not continuing to traverse after firing. The key skill for the layer was to be able to keep the telescope and hence the gun continuously on correct point of aim at a tank moving in his arc of fire.

The Number 1's job was to judge range and speed so that he could give the correct orders to his Number 3, and order corrections instantly. He also had to prioritise his targets and judge the moment to open fire. None of this was as easy as it sounds.

Besides the variety of military skills required of any soldier involved in direct fire against the enemy, and plenty of training in tank recognition, the main emphasis of anti-tank training was on gunnery and fire control. Units in UK undertook monthly live firing on anti-tank ranges, mostly using PP shot. Other training involved miniature ranges using 0.22-inch sub-calibre or coaxially mounted 0.303-inch Bren guns on more spacious ranges. Non-firing exercises were also vital to teach range estimation. Finally anti-tank gunners were routinely trained to use captured enemy equipment.

Generally, the batteries of an anti-tank regiment in an infantry division were assigned one to each infantry brigade with their battery commanders receiving orders from the brigade commanders. This left one in reserve in a 4 battery regiment. Brigade commanders and the CRA would coordinate the anti-tank guns and any anti-tank tasks for field guns. At the beginning of the war the brigade anti-tank companies were treated as another troop. Later it became usual for artillery anti-tank troops to be allocated to infantry battalions, with either the artillery troop commander or the battalion anti-tank platoon commander being the overall anti-tank advisor for the battalion. Battery commanders had this role at brigade level and the anti-tank regiment commander at divisional level.

Corps anti-tank regiments' tasks included accompanying covering forces, flank protection with other arms, reinforcing divisional anti-tank layouts, give depth to the defence of a corps area, guarding HQs and administrative areas and defending bottlenecks on main Line of Communication.

Anti-tank guns were not decentralized to armoured regiments in armoured divisions. Their usual tasks were flank protection (armoured formations were likely to have open flanks), supporting the motorised brigade or establishing a fire base. SP anti-tank guns would accompany the reconnaissance regiment advance guard. With the motor brigade they would secure 'pivots' that provide the base for attacks. Unlike tanks, SP anti-tank guns did not use hull down positions, they sought defiladed ones. Of course there was sometimes a tendency for SPs to act as if they were tanks. However, they were far more lightly armoured, which also made them vulnerable to short range infantry anti-tank weapons.

The deployment principles for anti-tank guns were to site them with an uninterrupted (enfiladed) field of view over their arcs of fire. The need for surprise at the most effective range meant the ideal positions were defiladed that covered an obstacle. Effective fire meant concealment and surprise: camouflage, defiladed from enemy observation and dug-in whenever possible. Digging was often easier said than done, it took 12 - 15 hours to dig-in a 17-pdr. Defilade usually meant engaging tanks from the side, which presented the largest target and had less armour than the front, the first Pz KfW Mk VI Tigers were destroyed by 6-pdr fire from their flank at ranges between 500 and 900 yards.

All-arms planning and coordination was vital and artillery anti-tank guns were allocated to where the ground was most suitable for enemy tanks. The need for both concealment and for the detachment to administer themselves meant that villages and woods were preferred to positions in the open. However, anti-tank guns were vulnerable to infantry attack and this meant that they were generally sited within defended localities. Anti-tank guns were only one part of the anti-tank defences. The other parts were obstacles, both natural and man-made, and anti-tank mines.

Natural obstacles were defined as waterways at least 4 feet deep, slopes greater than 1 in 1 (eg railway embankments and cuttings), thick woods with trees greater than 18 inches diameter and close enough together to prevent tanks passing between them and built-up areas that could be turned into anti-tank locations. Artificial obstacles include those with long preparation times such as concrete blocks, ditches and demolitions, and quick ones using mines and No 75 grenades.

British doctrine classed minefields as protective, defensive or tactical. Protective minefields were designed to prevent penetration of locations by the enemy and were planned in conjunction with anti-tank guns. They did not obstruct counter-attack routes and had gaps for vehicles to move through. Defensive minefields prevented penetration between locations. Tactical minefields were designed to canalise enemy movement. The overall tactical and defensive minefield layouts were ordered by the divisional commander in accordance with his counter-attack plans, their detailed siting was coordinated with anti-tank (either the CRA or anti-tank regiment commander) and Royal Engineers who were responsible for their detailed design and for laying them. If counter-attacks were to involve tanks then they would also be coordinated with the armoured commander. Brigade commanders coordinated in their brigade areas in accordance with the divisional plan.

In defence, the main threat was considered to be massed tanks in open terrain, so this is where the anti-tank effort concentrated. Anti-tank guns could have several positions. The normal task given to an anti-tank gun was to destroy tanks within their arc of fire. This arc could be wider than the guns top traverse, for example the standard gun pit for a 6-pdr provided an 110 degree arc. Guns would usually be given a second position with a different arc, this meant that guns could be concentrated onto the zone where the primary threat appeared. The use of various arcs and second positions enabled fire to be concentrated. They were also given alternative positions to used in order to avoid being neutralised. Anti-tank defences were based on the principle that penetration of defensive localities by enemy tanks was unacceptable, so guns were sited in depth as well as being mutually supporting with the objective of taking a successive toll of attacking tanks.

For covering force tasks to delay the enemy approach and deny observation and surprise, divisional anti-tank guns could be allocated to brigade battle outposts in front of a defensive position. However mobile troops controlled by corps or division could have anti-tank guns from a divisional reconnaissance regiment or a corps anti-tank regiment.

In an advance the infantry division reconnaissance regiment relied on its own anti-tank guns, but could be allocated artillery anti-tank guns for special tasks such as seizing vital ground. However, a battalion size advance guard for a brigade would usually be allocated an anti-tank troop, although the battalion's own anti-tank platoon would usually accompany the vanguard company. Towed 17-pdr were not allocated to an advance guard but SP ones could be. Towed guns were deployed with flank guards, usually dispersed in the column, although picquetting could also be used and movement could be by troops leap-frogging each other. Doctrine was that anti-tank guns were never unemployed in mobile or fluid operations.

In attack anti-tank guns provided protection during form-up, attack and consolidation. They also protected the flanks if corridors formed into the enemy position. A reinforced battalion attack could be allocated a complete anti-tank battery. The attack plan included positions for anti-tank guns in consolidation, doctrine was that guns should arrive on the captured objective within 15 minutes of its capture. The battalion's guns were first forward, SP 17-pdr were considered too big and not suitable for the most forward positions, but were used on flanks until 6-pdrs arrived, when the SP 17-pdrs went into reserve. Towed 17-pdrs were used in depth.

When deploying to consolidate after an attack, the troop commanders decided the standard battle drill, section commanders selected gun sites, troop commanders adjusted gun positions as required. The final coordination was by the anti-tank battery commander and the troop that had protected the forming up point (FUP) did not come out of action or move forward until ordered by the battery commander.

Although the original portee anti-tank tactics could be considered tank hunting, after this it was not widely used. SP anti-tank guns did sometimes manoeuvre to engage tanks otherwise beyond engagement, for example in turret down positions. However, they needed a suitable escort. Nevertheless in the final stages of the Normandy campaign SP anti-tank guns, directed by Air OPs, were used to pursue and attack enemy tanks that were breaking engagement and withdrawing.

The evolution, ebb and flow of anti-tank tactics in desert is an extensive subject and not fully addressed here. Suffice to say it was a product of the circumstances. One feature was close collaboration between anti-tank batteries and the divisional machine-gun battalion, MMG fire could force tanks to close down and protect the anti-tank guns against infantry. The underlying problem for the 2-pdr was not just its inability to be effective against the front armour of German tanks but also its limited range and the space of the desert in the face of massed attack.

However, anti-tank tactics could be said to have been sorted out by the time of the Medinnine battle in Tunisia. In this action 30 Corps was attacked by 10, 21 and part of 15 Pz Divs having had a few days to prepare their positions. The anti-tank defence had been fully coordinated, including guns sited to destroy tanks and not directly protect infantry positions. After four major attacks on 6 March 1943 the Africa Korps abandoned the action, it was not just the anti-tank guns but heavy concentrations of indirect fire as well.

Thereafter British anti-tank was mostly concerned with defeating armoured counter-attacks. A Corps HQ in Italy reported the following effective tactics:

'(a) The first weapon to arrive on the objective, which is capable of dealing with enemy tanks, is nearly always the tank itself, and there is no question of it being withdrawn until it is relieved by anti-tank guns, either SP M10s or towed guns. It must therefore stay in a hull down position in the forward infantry locality or only just behind it. The infantry must bear in mind that, except in a village and town fighting when it is permisable to retain a few tanks forward, it is essential that tanks are released as soon as this is tactically possible.

(b) The next weapon to come up should be the SP M10, and it should be kept well forward for this purpose. It is capable of moving over bullet-swept country, and can function without being dug-in. Using its mobility, it can move from one side of the objective to the other, and so quickly counter any enemy tank threat. An M10 should rarely remain stationary for any length of time unless under cover. Its mobility makes it so much harder to knock out than a dug-in gun that can be located and neutralised. The arrival of the M10s should enable the tanks to be released to proceed to a forward rally.

(c) It will often be impossible to move forward the towed guns until after dark, or even if they could be got forward in might be impossible to dig them in. When they are emplaced the M10s can withdraw to forward rally, and the tanks can be released for maintenance.'

Field artillery used as anti-tank came to prominence in the desert in 1941-2 where up-armoured German tanks were mostly immune to 2-pdr and 37-mm anti-tank guns. Once 6-pdrs became available then 25-pdrs were no longer needed in the anti-tank role, except for self-defence. In Malaya 4.5-inch howitzers direct firing HE proved effective against Japanese tanks.

40-mm LAA guns firing AP were also used successfully on a few occasions, 40-mm AP was fired as aimed single rounds not bursts. In 1942 its Forward Area Sights Mks 1 - 3 were modified to make them suitable for engaging armoured vehicles. Also in that year Army Training Memorandum No 43 explained the anti-tank role of 40-mm. Engagements could be controlled by the predictor, or at the gun using the Stiffkey Stick. A Bren LMG was coaxially mounted for training.

Field artillery readied themselves for anti-tank through a set of 'states of readiness'. The usual state for a battery was 'Normal', when tanks were not expected to appear, however, anti-tank defence plans were made and range cards prepared. 'Prepare for Tanks' was ordered when a tank attack was considered possible, typically observers were posted and ammunition prepared but the guns continued their indirect fire tasks. 'Tank Alert' meant that a tank attack was considered imminent and the guns were loaded. When enemy tanks arrived the troop Gun Position Officer ordered the guns to engage within their planned sectors, and engagements then devolved to the Numbers 1 of each gun.

Indirect fire artillery was also effective, concentrations would knock-out a few tanks but heavy concentrations also caused enemy tank attacks to stop and withdraw. However, this had little success in the 1941-2 period in the desert because of lack of guns and the weak procedures for unplanned artillery concentrations. Nevertheless, while tank losses from indirect fire might be small, they forced tanks to close down, forced them to withdraw when they needed to refuel and rearm, and if concentrations were sufficiently large could cause attacks to be abandoned. However, circumstances could enhance the effects:

The question often arises as to why the British Army did not use their 3.7-inch HAA guns in the primary anti-tank role as the Germans used their 8.8-cm FLAK. 3.7-inch was used its secondary anti-tank role on a few occasions but there are probably several reasons why it was not generally used in a primary anti-tank role:

The general conclusion is that 3.7-inch HAA guns were seldom deployed in areas where they might have a secondary anti-tank role. Using them in a primary anti-tank role might have seemed a good idea to junior officers in the front line. However, the senior officers who actually commanded AA formations and usually 'owned' HAA units had a wider perspective of the war and most likely considered that the air threat was more significant. They were probably right.

In 1949 anti-tank ceased being a RA task and all responsibilities were transferred to the Royal Armoured Corps (RAC) and infantry. However, the was a resurrection almost 30 years later when all Swingfire ATGM, fired from FV 438 and Striker armoured SP launchers, were removed from RAC and infantry units and organised in divisional anti-tank batteries RHA. Each battery having 36 launchers in 6 troops. This lasted until the mid-1980s.

Military Training Publications (MTP)

MTP 19 Tactical Handling of Anti-tank Regiments, 1939.

MTP 42 Tank Hunting and Destruction, 1940.

MTP 59 Anti-tank Gunnery, 1943.

Middle East Training Publication (METP)

METP No 12, Part 4 Notes on Anti-tank Shooting - Field Equipment (undated) replaced by Part 4A, June 1942.

Artillery Training (AT)

AT Vol 1 Tactical Employment, Pam 9 Anti-Tank Tactics, 1943.

AT Vol 2 Deployment, Pam 5 Deployment of an Anti-Tank Regiment, 1944.

AT Vol 3 Field Gunnery, Pam 9 Anti-Tank Gunnery, 1943.

Range Tables

6-pr, 7-cwt Guns, Mks 2 & 3 AP, 2 CRH, Full Charge, 1942.

6-pr, 7-cwt Guns, Mks 4 & 5 APCBC, 6 CRH, Full Charges, 1943.

17-pr Guns, Mks 1 & 2 AP or APC, 2 CRH, Full Charge, 1942.

3-in Gun M7 on Carriage M10 AP M79, APC M62, and HE M42, 1944.

Handbooks (HB)

HB for the Ordnance, QF 2-pr, Mks 9 & 10 on Carriage, 2-pr, Mks 1, 2, 2A, 2B and 3A, Land Service, 1938.

HB for the Ordnance, QF 6-pr 7-cwt, Mk 2 on Carriage, 6-pr, Mks 1, 1A & 2, Land Service, 1942.

HB for the Ordnance, QF, 17-pr, Mk 1 on Carriage, 17-pr, Mk 1, Land service, 1943.

Copyright © 2004 - 2014 Nigel F Evans. All Rights Reserved.